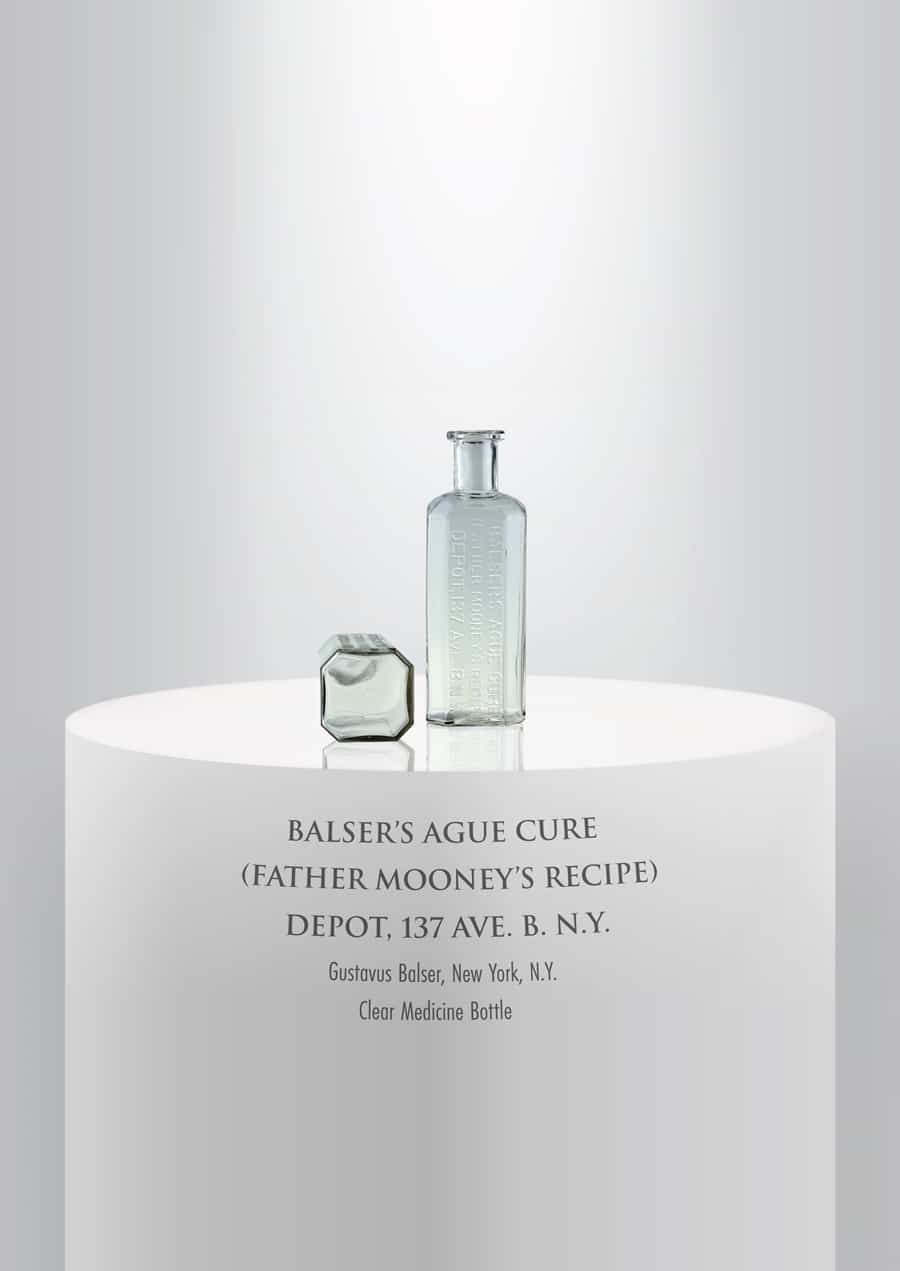

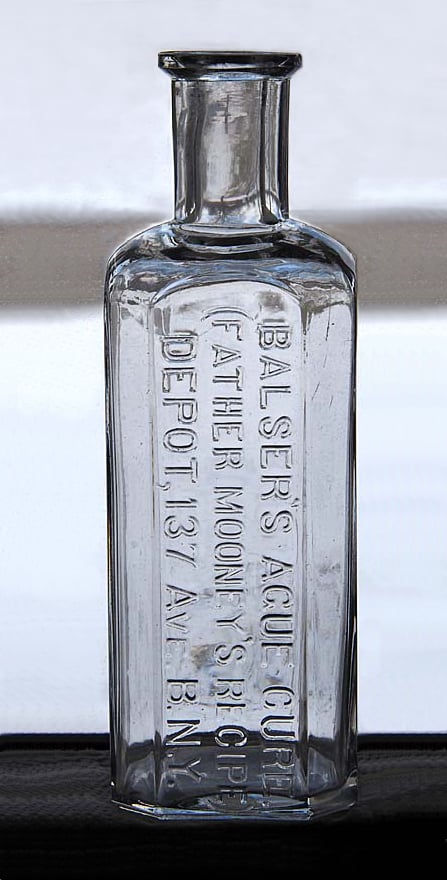

Balser’s Ague Cure. (Father Mooney’s Recipe) Depot, 137 Ave. B. N.Y.

Balser’s Ague Cure.

(Father Mooney’s Recipe)

Depot, 137 Ave. B. N.Y.

Gustavus Balser, New York, N.Y.

Clear Medicine Bottle

Provenance: Bob Jochums Collection

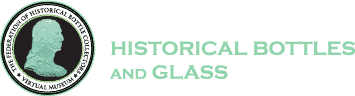

Our sparkling, clear subject bottle is 2 inches square and 6¼ inches tall. The corners are broadly chamfered, and it has a square band tooled collar. The embossing, in three lines from top to bottom on one side, utilizes a sans serif typestyle. The base is smooth. Matt Knapp, in his online PDF file titled Antique American Medicine Bottles 2015, lists a Balser’s Wild Cherry Cough Balsam with the same embossed address. “Depot” may have meant a type of building or property created for a specific purpose, such as locating Balser’s products.

Gustavus Balser, born in Germany in 1843, emigrated to the United States with his parents at the age of three. By the age of eleven, he and his family lived in a three-story brick and stone structure at 137 Avenue B in the East Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan in New York City, where he would ultimately create and sell his products and live until his death at the age of 76 in 1919.

In 1868 Balser married Anna Mary Engel, also an immigrant from Germany. Reports vary, but they may have had four children, only two of whom lived to adulthood.

The Federal decennial census from 1900, when Balser was 57 years old, states that Wray B. France, age 23 and born in the United States, was a boarder at the Balser home. France and Balser were both listed as druggists, and France became Balser’s son-in-law when he married Anna A. (Annie) Balser, the youngest daughter of Gustavus and Anna Mary. By 1910 Gustavus and his wife had a two-year-old granddaughter, Elliot B. France.

Tragedy befell Gustavus and Anna Mary when in 1904, their eldest daughter, Katherine Balser, age approximately 31, died in what is known as the General Slocum disaster. A pleasure steamer providing excursions in the New York harbor vicinity, the SS General Slocum caught fire while on the East River. Reports vary that between 863 and 1021 lives were lost of the 1331 people (mostly women and children on a picnic outing from St. Mark’s German Lutheran Church) on board. It was New York City’s worst disaster until September 11, 2001.

Research reveals scant information about Balser’s business dealings. Both known products he produced are embossed with the address of his home, which was also most likely his factory (in the basement) and his shop (on the first floor or the street beneath awnings, as was common in the neighborhood).

Not a single English-speaking newspaper advertisement for his products has been found. By 1860, the population of East Village had grown to 73,000, becoming a thriving center of German-American life and culture. Balser’s address was on Avenue B across from Tompkins Square Park, which was the “city center.”

Because most new immigrants were German speakers, East Village and the Lower East Side became known as “Little Germany” (Kleindeutschland). The neighborhood had the third largest urban population of Germans outside Vienna and Berlin, with Balser’s products prominently displayed and sold by word of mouth among his German brethren.

In 1884, Balser was a member of the Executive Committee of the National Retail Druggists Association. In 1890, Balser was a trustee of the New York College of Pharmacy.

Balser’s ague product was most likely proffered as a remedy for the treatment, cure, and perhaps even prevention of ague, or malarial fever. Also termed swamp fever, the shakes, chill fever, or marsh fever, ague was characterized by fairly regular intervals of intense chills, sweating, and high fever.

Ague was long believed to result from the inhalation of miasma, a poisonous vapor or mist containing particles (miasmata) from “rotting corpses, the exhalations of other people already infected, sewage, or even rotting vegetation.”

Balser’s Ague Cure, for which a label was designed and submitted to the U.S. government in 1875 for registration, was timely and perhaps effective. In 1876, Robert Koch proved that a bacterium (Bacillus anthracis) caused anthrax, thereby bringing a definitive end to the miasmal “bad air” theory. The treatment of ague, while due to a protozoan transmitted by mosquitoes and not a bacterium, was imperfectly understood into the final two decades of the 19th century.

For the working class German-American, ague could have been treated inexpensively with patent medicines like Balser’s, which may have contained quinine—the predominant malarial medication until the 1920s. Another option was a costly visit to a physician who might choose to employ the barbaric technique of bloodletting as his treatment of choice.

Primary Image: Balser’s Ague Cure imaged on location by Alan DeMaison, FOHBC Virtual Museum Midwest Studio.

Research: Bob Jochums, Berkeley Lake, Georgia

Support Image: Balser’s Ague Cure exterior setting. Greg Spurgeon, North American Glass.

Support Image: Balser’s Ague Cure and a 3-bladed fleam – Bob Jochums.

Support: Reference to Ailments, Complaints, and Diseases in the 1700 and 1800s by Geri Walton, 2014.

Support: Reference to Miasma theory.

Support: Reference to The Causes, Treatment, And Cure of Fever and Ague, and Other Diseases of Bilious Climates by Charles Osgood, M.D., thirteenth edition, New York, 1865 (first printing, 1840).

Support: Reference to Death and miasma in Victorian London: an obstinate belief; The British Medical Journal; December 22, 2001.

Support: Reference to Kleindeutschland: Little Germany in the Lower East Side by Dr. Richard Haberstroh, copyright 2022.

Join the FOHBC: The Virtual Museum is a project of the Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors (FOHBC). To become a member.