Dr. FC Atwood’s Colic Cure No. 1 & No. 2 Dose 1/2 Oz. Laboratory New Haven Conn.

No. 1 & No. 2

Dr. F. G. Atwood’s Colic Cure

Dose 1/2 Oz.

Laboratory New Haven Conn.

W.T.Co. 6 U.S.A.

Dr. Frank G. Atwood, New Haven, Connecticut

Matched Pair Orange Amber Medicine Bottles

Provenance: Bob Jochums Collection

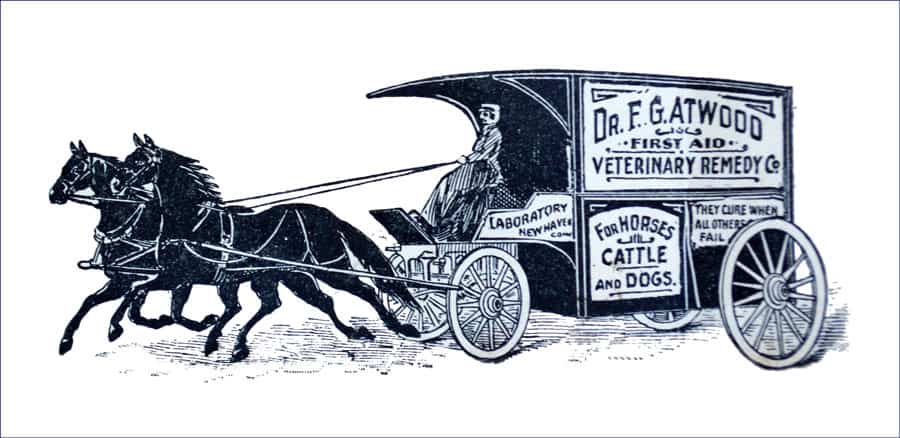

Dr. F. G. Atwood was a pioneering veterinarian with a laboratory in New Haven, Connecticut. He sold his First Aid Veterinary Remedies primarily for horses, cattle, and dogs. None of his products were genuine unless they contained his portrait photograph, which he used for his trademark. He was also known for his state-of-the-art Operation Room for horses and dogs and his Operating Table for horses.

Veterinary medicine in America in the early 19th century was folk medicine: knowledge of nameless origin that had been passed on orally from one generation to the next. With the advent of newspapers affordable to working-class citizens, veterinary care of livestock became “popular” medicine as information was acquired through the media. Professional care finally made an entrance in the final decade or two of the 1800s when formal medical education was legally sanctioned at colleges and universities and regulated by the states.

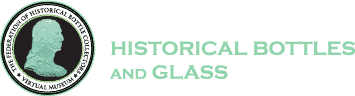

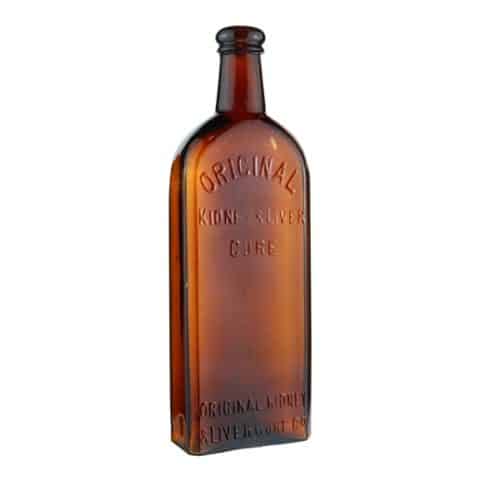

Our display pair of orange-amber veterinary colic cure bottles are prominently embossed horizontally in seven lines in a sans serif typestyle on a single flat side of both bottles. The only difference in the embossing of the pair is that one bottle is embossed ‘NO. 1’ while the other bottle is embossed ‘NO. 2’ at the base of the neck. Each bottle measures approximately 5 inches tall x 1 ¾ inches square and has a nicely tooled square band collar on an attractive neck.

The additional embossed copy is ‘DR. F. G. ATWOOD’S’ (2nd line), ‘COLIC CURE’ (third line), ‘DOSE ½ OZ.’ (fourth line with an enlarged “1/2”), ‘LABORATORY’ (fifth line), ‘NEW HAVEN’ (sixth line) and ‘CONN.’ (seventh line). All copy is center-justified in a slightly raised, tall, tombstone-shaped panel.

The base embossing occurs in three lines and reads ‘W.T.CO. 6 U.S.A.’ The “6” is positioned in the center of the convex and concave “W.T.Co.” and “U.S.A.” copy. The “6” indicates that the volume of each bottle is six ounces. This method of identifying Whitall Tatum Company products commenced in 1901 and continued for approximately twenty years.

Colic Cures

Although the ingredients of colic cures were often not known, most contained 60% or more alcohol (most likely a solvent and a preservative as the small dose administered would have had little beneficial effect on a horse, even after several doses) and some narcotic, usually opium. When known, the ingredients of the two bottles (No. 1 and No. 2) were often very similar. One competing product had the same amount of the primary ingredient, twelve grains of opium per ounce, in each bottle. Not all veterinarians putting up colic cures did so in two bottles and such a practice may have been a sales ploy and an attempt to control the dosing of the narcotic.

Most packages of colic cures came with a glass measuring vial and the suitable dose was either one vial or thirty drops of the product. The dosing of No. 1 and No. 2 was alternated with the time between doses varying from eight to thirty minutes depending on the purveyor’s instructions as well as the severity of the colic.

Veterinary Medicine

Education in and the professionalization of the field of veterinary medicine in the 19th century was not a formal construct until the 1890s. Up until that time and enduring into the 20th century, the preponderance of veterinary medicine was practiced by horsemen and farmers or ranchers on their own animals, with newspaper articles and advertisements (handbooks, patent medicine almanacs, and brochures) serving as a national clearinghouse for popular veterinary knowledge. Horses and livestock were vital to flourishing rural American families of this era and veterinary medicine knowledge was quite limited. A frequent topic of conversation between farmers and others reliant on livestock was the maintenance of the health of the animals on which the value of their land and crops was dependent.

Colic is a general term for abdominal pain. That pain, however, could be the result of many gastrointestinal disorders, of which several can be potentially fatal.

Remedies of the era may have included the narcotics opium or laudanum for their comforting and sleep-inducing properties. Cathartics (substances that accelerate defecation), such as aloe, croton oil, and castor oil, were used to purge blockages in the colon. A mixture of lard, soot, and cayenne pepper might have also been recommended. Additional “medicines” included pine tar, salt, soap, vinegar, ammonia, and mercuric oxide administered orally to a very displeased animal.

Treatments and remedies dispensed to horses in the 1890s make little sense today unless they are considered within the context of 19th-century human medicine. Veterinary medicine for the treatment of “dumb animals,” despite their value and importance to a farmer’s livelihood, lagged behind the progress that had been made in the field of medicine for mankind.

Dr. Frank G. Atwood

Frank Goodwin Atwood was born on February 24, 1875, in Woodbury, Connecticut. Of English descent, his ancestors came to the New World as passengers on the Mayflower, originally settling in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

In the latter half of the 19th century, veterinary science was typically practiced by self-taught men who were instructed by other self-taught men. Not until the 1890s did primitive veterinary practices begin to give way to the emergence of the scientifically trained veterinarian. A hindrance to this progress was the national government’s failure to encourage formal veterinary schooling. At a time when outbreaks and epidemics of animal diseases were widespread, the Department of Agriculture had previously shown apathy toward the establishment of a veterinary division.

Frank G. Atwood sought his training at a time when professional veterinary education was beginning to become the norm for new practitioners. A graduate of the Connecticut Agricultural College and then the Department of Veterinary Medicine and Surgery of the University of Toronto in 1896, Atwood launched his private veterinary surgery practice. Finding that his chosen career would benefit from additional training in laboratory medicine, he completed a post-graduate course in the Department of Medicine of the Yale Medical School (1898) as well as supplementary studies in general medicine and surgery at Johns Hopkins University.

In 1898, at the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, a short period of armed conflict a few months following the explosion and sinking of the armored cruiser USS Maine in Havana Harbor in Cuba, Atwood became connected with the medical department of the United States Army. Because of the diversity of his medical training, Atwood provided care to soldiers in Cuba and then in Washington, D.C. until May 1899.

Returning to his veterinary surgical practice, Dr. Atwood garnered a highly regarded status in professional circles. His service included the founding of the New Haven Veterinary Hospital in 1907.

Being broadly and recently educated as well as very strong-willed, Atwood at times found himself in disagreement with other veterinarians and politicians who adhered to practices that relied on folk remedies and outdated medical conventions. Dr. Atwood advocated state-of-the-art lab testing and the incorporation of progressive changes to the practice of veterinary care.

Not hesitant to promote himself and his products, Atwood’s correspondence envelopes were embellished with the following claim: “Dr. Atwood’s Veterinary Medicines are scientific compounds, not accidents, but the results of scientific research. Leading horsemen endorse them as being the best in the world.”

Atwood chose to pay particular attention to animal diseases that could be transmitted to man (zoonotic diseases), sometimes resulting in severe illnesses and, in some cases, death. When powerful elected or appointed individuals (Connecticut’s Commissioner of Domestic Animals and the governor of Connecticut, for example, neither of whom were experts in veterinary practice) neglected to act to avoid these diseases, Atwood took civil action for the public good.

Declaring the superiority of his training and practice, Atwood’s correspondence envelopes asserted, “Dr. Atwood has devoted more time and money to the study of diseases and treatment of domesticated animals than most Veterinarians in the United States.”

Atwood was a member of the American Public Health Association, the United States Stock Sanitary Association, a life member of the Connecticut Dairymen’s Association, and served as the president of the Connecticut State Veterinary Medical Association.

He died at his home of a heart attack on September 14, 1936, at the age of sixty-one, having earned recognition as one of the most capable veterinary surgeons in Connecticut. Dr. Atwood was survived by his widow and two daughters.

Primary Image: Dr. Atwood’s Colic Cure bottles were imaged on location by Alan DeMaison, FOHBC Virtual Museum Midwest Studio.

Research: Bob Jochums, Berkeley Lake, Georgia, Michael W. Smith, DVM, Lithonia, Georgia and Stan Tart, DVM, Kernersville, North Carolina.

Support: Reference to Frank G. Atwood, D.V.S., Modern History of New Haven and Eastern New Haven County, Volume II, Pages 704-705, 1918.

Support: Reference to Veterinary Roundtable by Mike Smith, DVM, FOHBC Bottles and Extras, Winter 2003, Page 42.

Support: Reference to Home Cures for Ailing Horses: A Case Study of Nineteenth-Century Vernacular Veterinary Medicine in Tennessee by Anthony P. Cavender and Donald B. Ball; Agricultural History, Vol. 90, No. 3 (Summer 2016), pp. 311-337.

Support: Reference to Livestock Doctors, 1850-1890: The Development of Veterinary Surgery by Earl W. Hayter; The Wisconsin Magazine of History, Spring, 1960, Volume 43, No. 3, pp. 159-172.

Support: Reference to Colic in Horses: Types, Symptoms and Treatment published by Foran Equine, July 5, 2017.

Join the FOHBC: The Virtual Museum is a project of the Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors (FOHBC). To become a member.