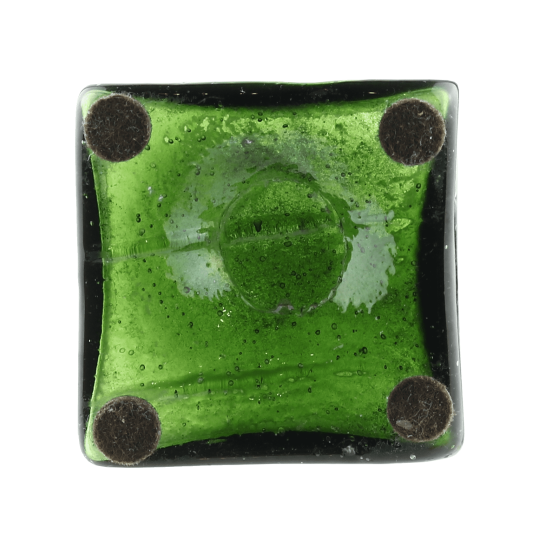

Snuff Attributed to Connecticut

Snuff Attributed to Connecticut

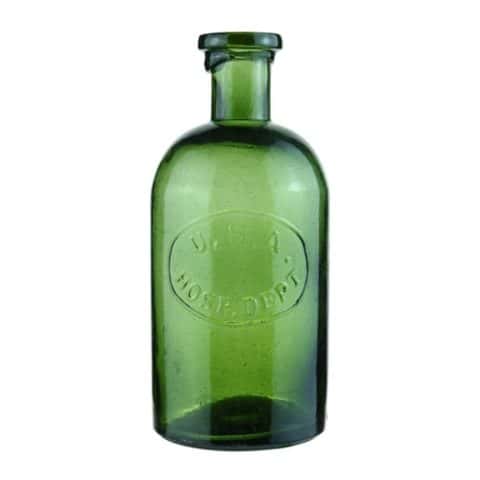

Vibrant Green Snuff Bottle

Provenance: Richard S. Ciralli Collection

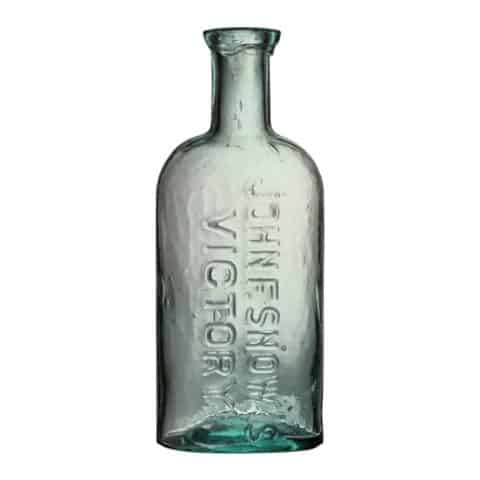

Our dip molded snuff is attributed to Coventry or Willington glassworks in Connecticut. The bottle has a sheared and fire-polished lip, early primitive dip mold, open pontil scar over some distinct embossed lines on the base. There are several rare base-embossed early snuffs with different markings but this one pronounces Connecticut. It was acquired from the late Stu Putney, a longtime New England collector from Connecticut known for his eye for the very best. The piece measures 4 3/8” high by 2 3/8” wide. The exceptionally rich blue-green glass is considered rare for any utilitarian wares.

The Connecticut source of reference is from American Bottles and Flasks and Their Ancestry by Helen McKearin and Kenneth M. Wilson (Commercial Containers-Snuff Bottles, p261), “One variety of square snuff that has been attributed to Connecticut—Coventry or Willington—on the basis of geographical distribution and family history has on the base two diagonal ribs to the right crossed by two to the left, placed asymmetrically.”

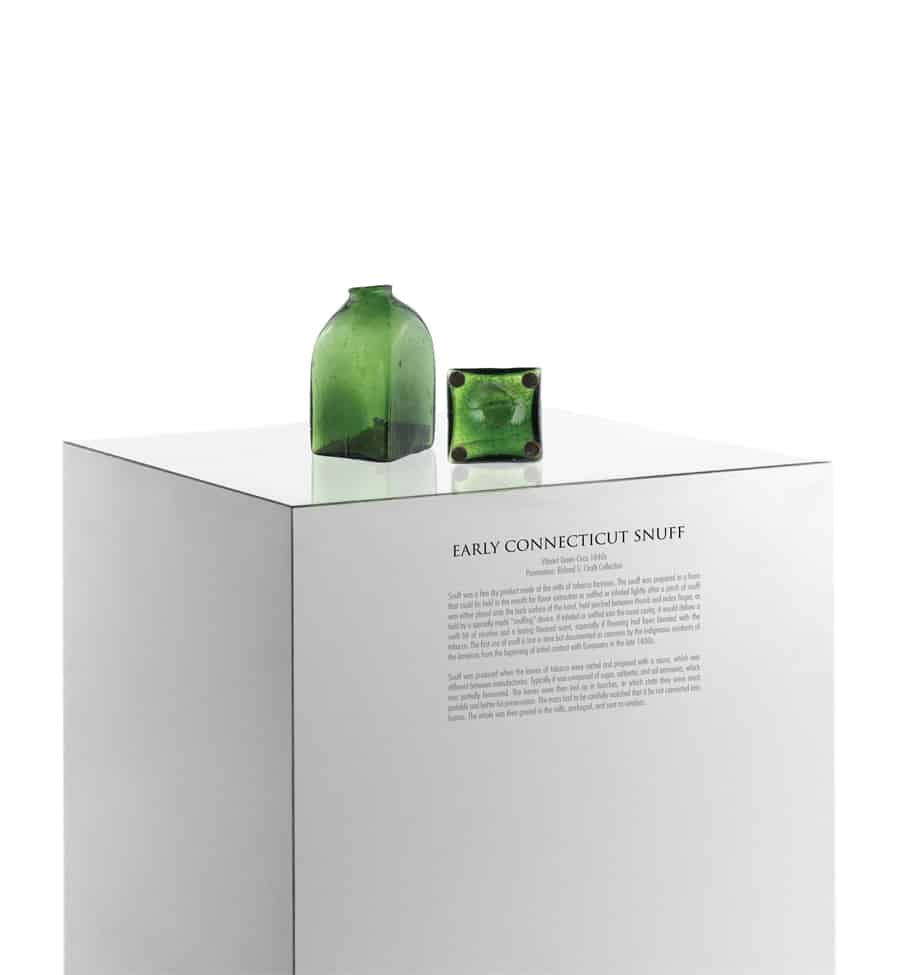

Snuff was a fine dry product made at the mills of tobacco factories. The snuff was prepared in a form that could be held in the mouth for flavor extraction or sniffed or inhaled lightly after a pinch of snuff was either placed onto the back surface of the hand, held pinched between thumb and index finger, or held by a specially made “snuffing” device. If inhaled or sniffed into the nasal cavity, it would deliver a swift hit of nicotine and a lasting flavored scent, especially if flavoring had been blended with the tobacco. The first use of snuff is lost in time but documented as common by the indigenous residents of the Americas from the beginning of initial contact with Europeans in the late 1400s.

Snuff was produced when the leaves of tobacco were sorted and prepared with a sauce, which was different between manufactories. Typically, it was composed of sugar, saltpeter, and sal ammonia, which was partially fermented. The leaves were then tied up in bunches, in which state they were most portable and better for preservation. The mass had to be carefully watched that it be not converted into humus. The whole was then ground in the mills, packaged, and sent to retailers. Many times aromatic substances and essential oils for scent and flavor were added like cinnamon, nutmeg, lavender, rose water, and bergamot.

Initially in Colonial America, there were few who used snuff, but many Germans and Frenchmen created a robust market. Eventually, in the mid to late 1700s, snuff became widely popular and just about every major glasshouse was filling orders for snuff bottles up until the 1880s or so. Snuff bottles were blown in Pitkin’s East Hartford glassworks as early as 1790.

There were different kinds of snuff manufactured, such a Maccoboy, Rappee, Lundy-foot, and Scotch snuff. There were other purposes in the Southern States where Scotch snuff was used such as to clean teeth or to excite a person’s gums after meals. Tons of snuff were shipped from Baltimore and New York to North Carolina and Georgia for this purpose. The snuff was also used for medicinal purposes and employed for destroying vermin on vines, plants, etc. During the latter part of the 19th century, snuff fell out of favor with the American populace.

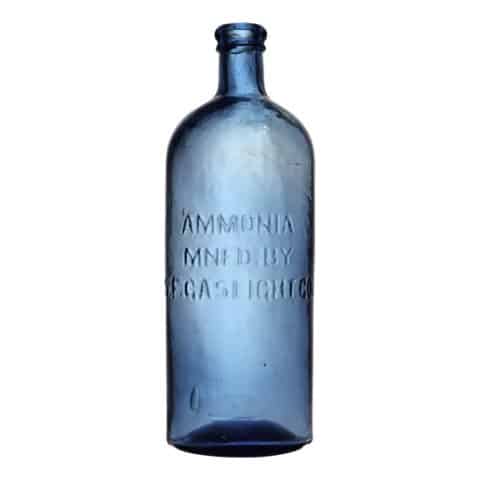

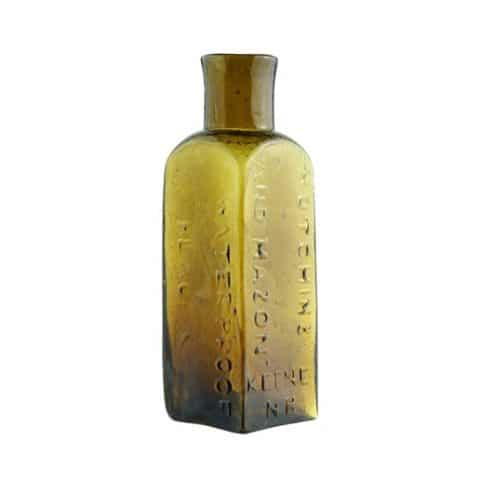

Most snuff jars or bottles have a distinctive, rectangular box-like appearance and wide mouth. Most of the early examples are pontiled. The glass colors are usually yellow olive, olive green, and greenish amber. Our museum example in a vibrant green is exceptional.

Many of the early jars have dot patterns on the base. The jars were filled before the labels were put on because of the strength properties of the snuff, so the packers needed the dots to know what went where. Most folks were illiterate back then, so dots were used instead of words. 5 and 6 dots would indicate heavy snuff for the mouth, which was not to be sniffed. A pontil marked, 1840-1850ss snuff may have two marks purposely made with iron rods on the bottom while a 20th-century machine-made snuff had the dots too.

Support: Reference to American Bottles and Flasks and Their Ancestry by Helen McKearin and Kenneth M. Wilson, Crown Publishers Inc., New York, 1978.

Primary Image: Connecticut Snuff Jar imaged on location by Alan DeMaison, FOHBC Virtual Museum Midwest Studio

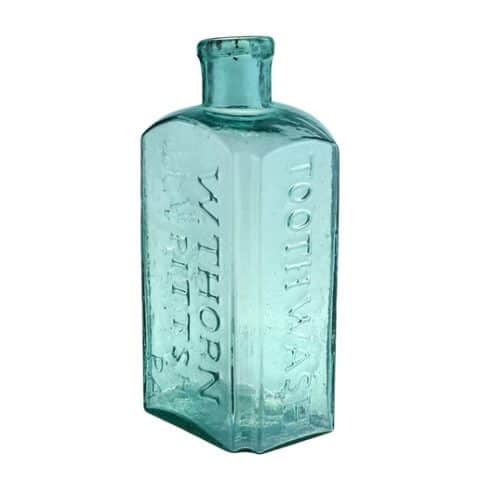

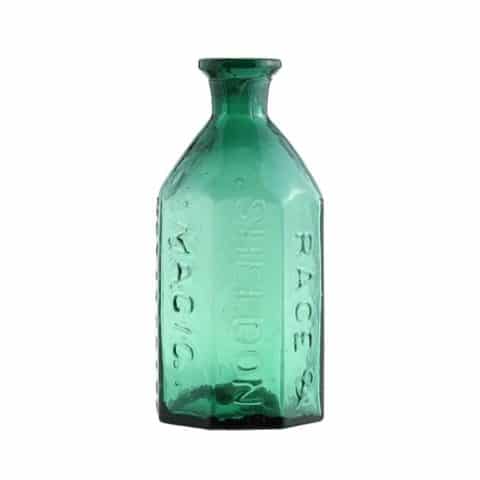

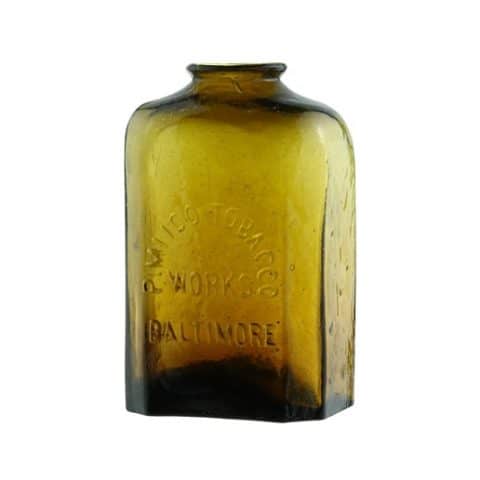

Support Image: Early unembossed snuff jars. Exterior image. Michael George collection.

Support Image: Early unembossed snuff jars. (in slide carousel with white background). Michael George collection.

Support image: Early unembossed snuff jars (in slide carousel). Charles and Jane Aprill collection.

Support: Reference to Snuff Boxes from the Knohl Collection

Support: Reference to Snuff Bottles on Peachridgeglass.com

Join the FOHBC: The Virtual Museum is a project of the Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors (FOHBC). To become a member.