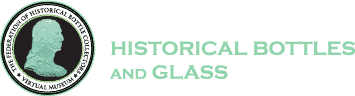

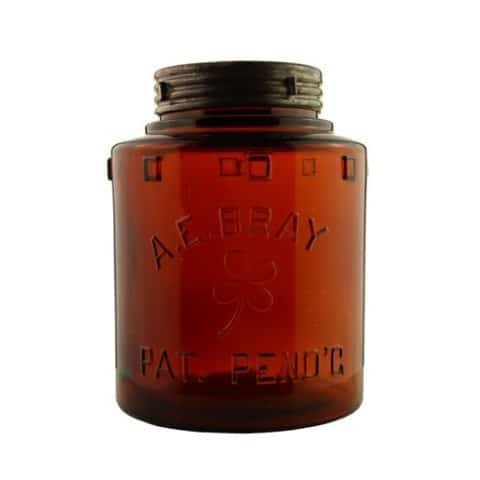

Frederick Heitz Glass Works St. Louis Wax Sealer

F H 6

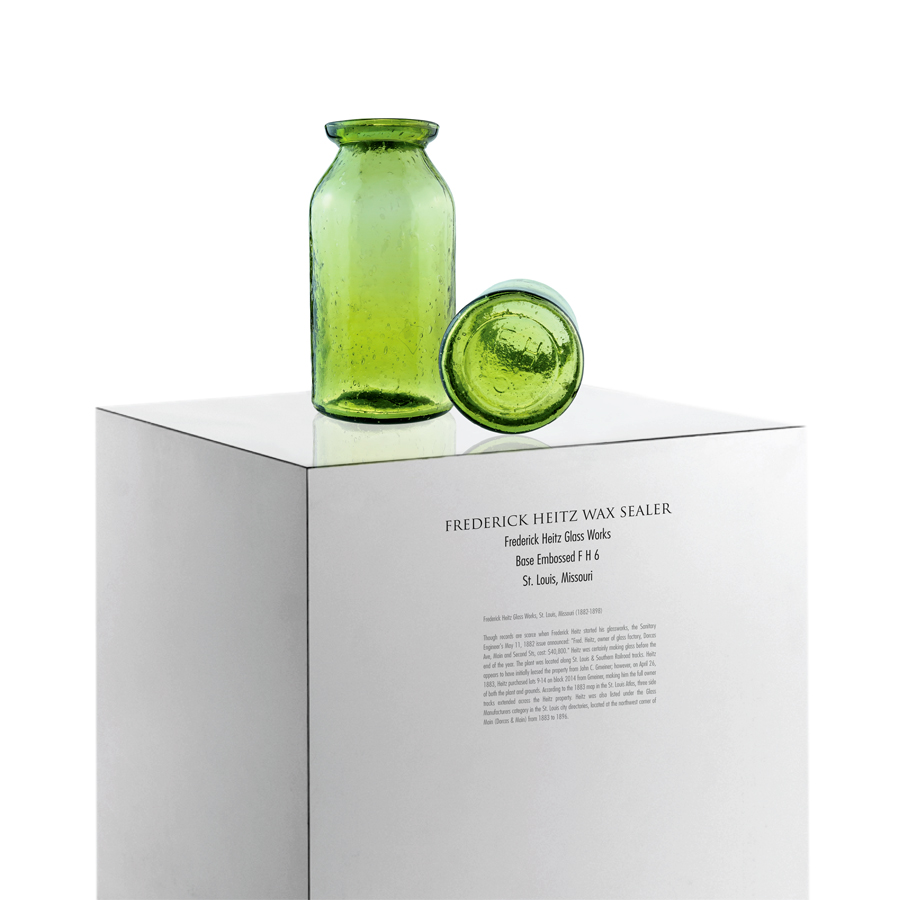

Frederick Heitz Wax Sealer

Frederick Heitz Glass Works, St. Louis, Missouri

Light Olive Green Quart

Provenance: Ron Hands Collection

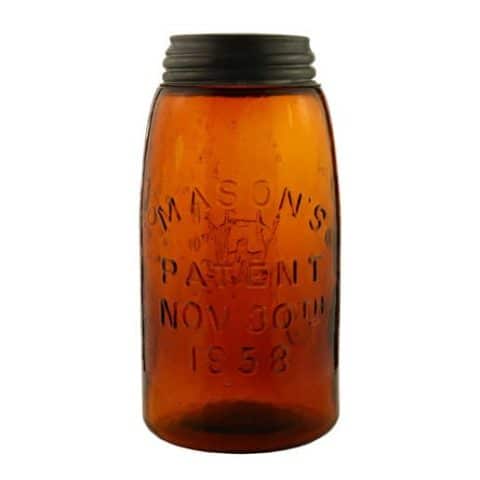

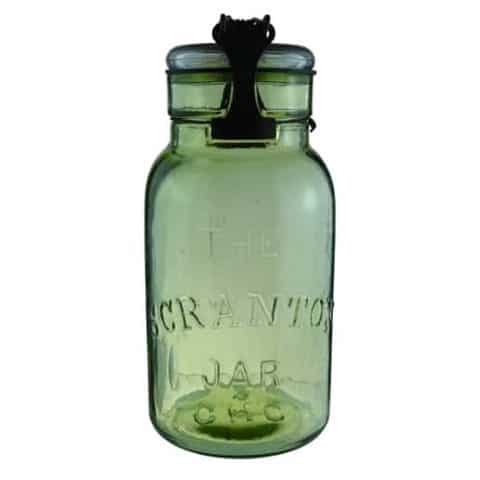

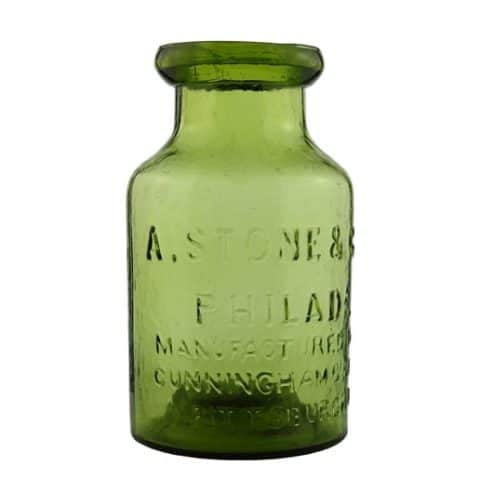

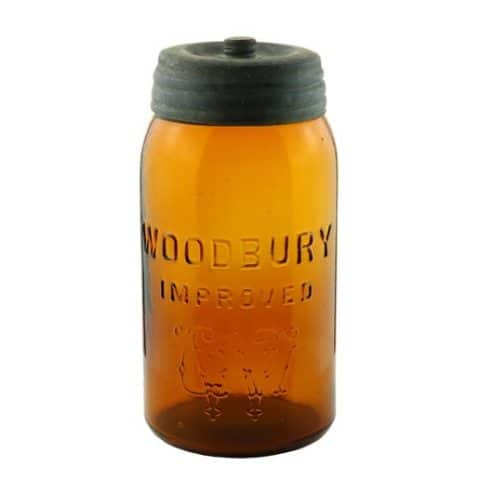

This remarkable quart wax sealer is base embossed ‘F H 6.’ For many years it was not known what the markings stood for. We now can attribute the jar to Frederick Heitz Glass Works in St. Louis, Missouri. The F.H.G.W. mark is also found on the bottoms of export-style pint and quart-size beer bottles, as well as on wax sealer type fruit jars, which are virtually identical in appearance to typical specimens made by factories in the American Midwest during the 1880s, especially at St. Louis, Missouri, Louisville, Kentucky, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and at several glass plants in the state of Indiana.

This best-possible example of a Frederick Heitz base embossed jar was made in a light olive-green glass that is full of character with its abundance of bubbles. The jar was purchased at the 2004 Mansfield, Ohio Bottle Show from Greg Spurgeon.

Frederick W. Heitz was born in Prussia in April 1829. He emigrated to the United States in 1848 and applied for American citizenship in St. Louis on April 29, 1868. He married Wilhelmina Thias on February 15, 1866.

Frederick Heitz Glass Works, St. Louis, Missouri

1882-1898

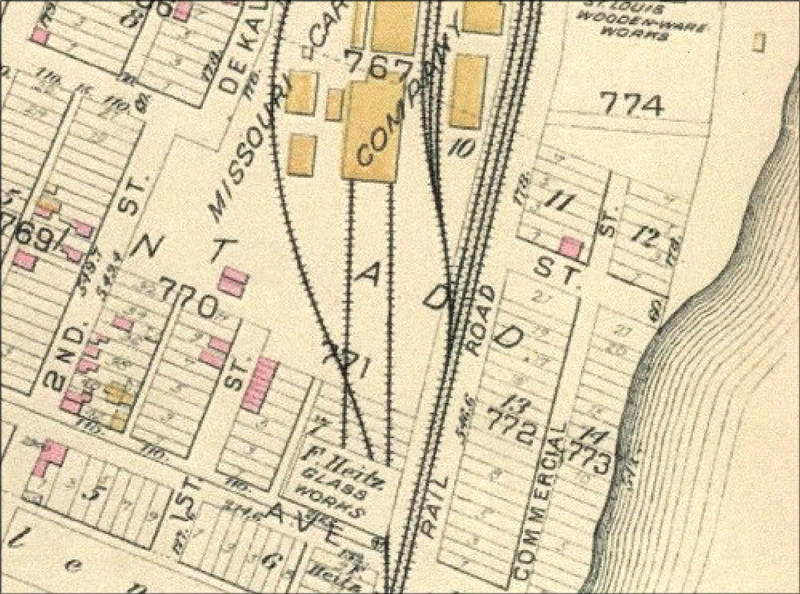

Though records are scarce when Frederick Heitz started his glassworks, the Sanitary Engineer’s May 11, 1882 issue announced: “Fred. Heitz, the owner of a glass factory, Dorcas Ave, Main and Second Sts, cost: $40,800.” Heitz was certainly making glass before the end of the year. The plant was located along St. Louis & Southern Railroad tracks. Heitz appears to have initially leased the property from John C. Gmeiner; however, on April 26, 1883, Heitz purchased lots 9-14 on block 2014 from Gmeiner, making him the full owner of both the plant and grounds. According to the 1883 map in the St. Louis Atlas, three side tracks extended across the Heitz property. Heitz was also listed under the Glass Manufacturers category in the St. Louis city directories, located at the northwest corner of Main (Dorcas & Main) from 1883 to 1896.

The early years of the business seem to have run smoothly, although one of Heitz’s workers, Henry Duckstein, sued Heitz for $10,000 for injuries at Heitz’s factory in 1884. Two years later, the Missouri Car & Foundry Works—a neighboring firm—was almost destroyed in a major conflagration, but the St. Louis fire department stopped the blaze short of Heitz’s glasshouse.

The business prospered. Heitz signed a deed of trust to the German-American Bank on August 14, 1894, as collateral for a loan to build a new factory and probably closed the old plant soon after that. On February 1, 1895, the Post-Dispatch announced that Fred Heitz had started the oven fires at his new glassworks and expected to begin production in about three weeks.

About a year earlier, Heitz had decided to enlarge his factory to compete with foreign bottle competition and closed the plant for renovation. The new plant cost about $100,000 and had an estimated production capacity of 500 gross bottles per day. Initial production was planned for beer and soda bottles. Heitz’s workers made all of the molds used at the factory. Heitz claimed that he had the largest “bottle tank” in the United States. The plant was known locally as the South St. Louis Glass Works—although it was always listed as the Frederick Heitz Glass Works.

Several things were occurring that would spell the demise of the firm. As noted above, Heitz had taken out a loan from the German-American Bank in August of 1894 to build the new factory. Soon after he opened the new plant, two things conspired to destroy the business. First, the market for fruit jars began to dry up. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch on September 18, 1895, printed the headline: “Jar Manufacturers Say the Custom of Preserving is Dying Out.” Housewives were apparently no longer canning as before, and retailers were reporting “large quantities of old stock on hand.” As a result, glasshouses lowered their prices and had a regular glass–jar war. The newspaper referenced E. F. W. Meyer Glass Co., who slashed their product prices. The Krenning Glass Co. followed, and the St. Louis Glass & Silverware Co. a few days later. Then, F. Heitz Glass Works and the Illinois Glass Co. joined in. This fierce competition was followed by a heavy price increase the following year, probably because the Ball Brothers, Marion Fruit Jar and Bottle Co., and a few other of the largest fruit jar producers had formed the Indiana Fruit Jar Sales Assn. in the spring of 1895 to control the price of fruit jars—freezing out the smaller jar producers like Heitz.

Since beer bottles were the primary product of the Heitz factory, this, by itself, would not have been a major issue. Second, however, the price of coal almost quadrupled. Though wood and coal were used at the furnace that heated the continuous tank at the new Heitz factory, it was fired primarily by coal. These developments with competition and access to the material were probably the Heitz glassworks’ major undoing.

In addition, Heitz had an interesting system that fell apart as railroad tracks ran through the glass plant—right into an area marked Storage of Stock and Materials coming from the Missouri Car & Foundry Co. plant to the east. This relationship enabled Heitz to unload raw materials directly into the plant and load glass directly onto railroad cars. In 1896, the railroad gave notice of its intention to reroute the tracks to the south of the factory.

The St. Louis Post Dispatch announced on June 27 that Heitz, along with Charles H. “Grate” (Grote) and August H. Thias, Heitz’s father-in-law, incorporated the St. Louis Switch Railroad Co., with a capital of $5,000, to build and operate a switch to create a new route into the plant. The plan failed. Although this is pure speculation, Heitz may have had another reason to retain the tracks through the factory. Glass houses used culet to prime the pots and tanks. The Missouri Car & Foundry Co. created a fair amount of glass slag in its processing. With the cars from the foundry passing directly through the Heitz plant, the factory had a virtually unlimited amount of cheap, possibly free culet.

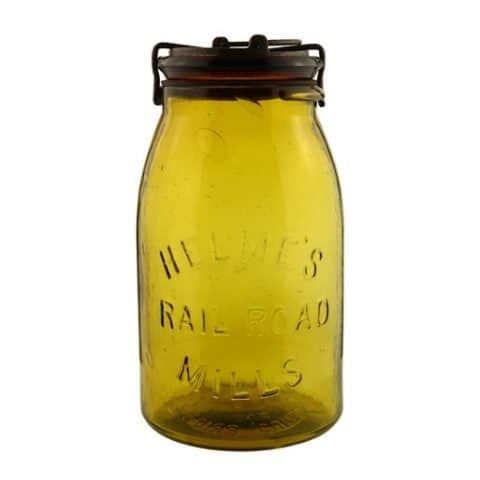

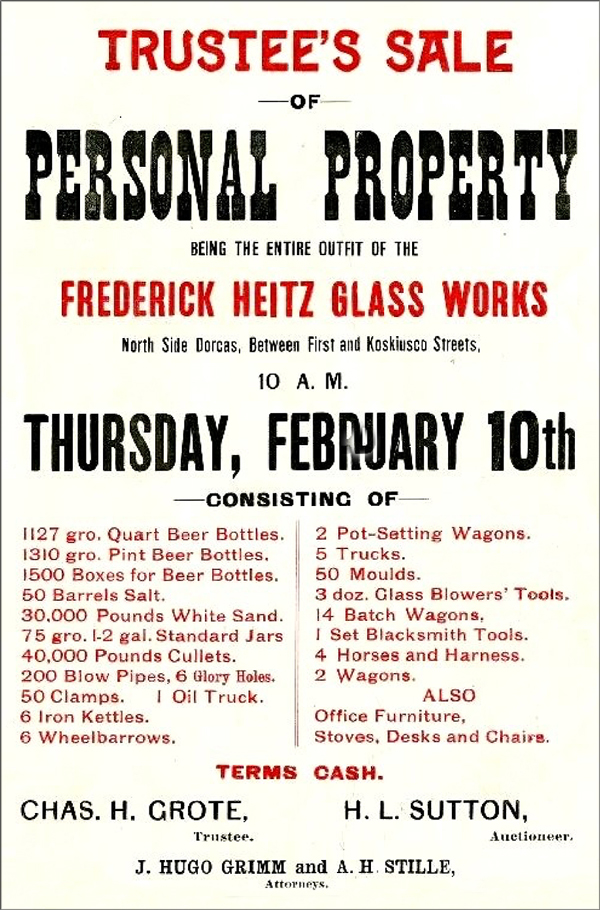

All of this was too much. In the May 12, 1897, edition of China, Glass & Lamps, it was announced that “Fred Heitz, the St. Louis beer bottle mfr., has placed his affairs in the hands of a receiver.” At the factory’s closing, Heitz operated one furnace with six pots and a single continuous tank with 13 rings. According to a flyer, a trustee’s sale of the “entire outfit” of the Frederick Heitz Glass Works, north side of Dorcas between First and Kosciusko Streets, was to be held on February 10, 1898. Included in the sale were “1127 gro. Quart Beer Bottles, 1310 gro. Pint Beer Bottles…75 gro. 1-2 gal. jars” along with boxes, blowpipes, 50 molds, horses, wagons, office furniture, and a variety of tools and other items associated with the trade. Despite the receivership, Heitz continued to operate the factory.

The Post-Dispatch ran the heading on January 23, 1898: “Seige Laid to Bottle Works—Mr. And Mrs. Heitz Barricade in an Office—There they Shouted Defiance to All Who Came Near for Two Days.” Apparently, Heitz had been forced into receivership “eight months ago,” and Charles H. Grote, the trustee for the sale of the plant, had placed Heitz in charge of the factory during the interim. Although some said that Heitz was only hired as a watchman, Heitz, himself, stated that he “was retained by Mr. Grote to superintend the works and look after the property because he had a knowledge of the business and also to sell the bottles.” When Grote claimed that Heitz was “selling the bottles on his own terms,” he sent two employees to evict Heitz from the premises. Heitz refused, bolting the windows, locking the doors, and preparing for a siege. Heitz and his wife “stocked the pantry with provisions, laid in a supply of fuel and incidentally got out all their old firearms and weapons of defense. Pistols and rifles were their mainstays, but knives, hatchets, and crowbars were not thrown aside as useless.”

John Schwartz, one of Grotte’s employees, tried to reconcile the situation peacefully, but Heitz met him at the door “with a revolver in his hand” while Mrs. Heitz stood behind him “at parade rest with a crowbar clenched in her hands.” Schwartz and John Meyers eventually caught Heitz outside and blocked his return to the office. The siege was over, and the Heitz family went home.

The 1898 insolvency signaled the end of production at the Frederick Heitz Glass Works. The March 23, 1898, issue of the Indiana State Journal (Indianapolis) provided a fitting epitaph for an unusual history: A year ago, when the Heitz Glass Company of St. Louis failed, and the works shut down, the “pot” was left full of molten glass. Recently the property was purchased, and the pot contains a solid piece of glass sixty-six feet long, twenty-two feet wide, and five feet thick, estimated to weigh almost 600 tons.

Frederick was the brother of Christian Heitz, an officer of the Lindell Glass Co. in St. Louis during the 1880s. Both men were in the grocery business after their involvement in the glass trade. Frederick Heitz died on May 31, 1907. He operated a grocery store and saloon at the time of his death.

Primary Image: Frederick Heitz Wax Sealer imaged on location by Alan DeMaison, FOHBC Virtual Museum Midwest Studio

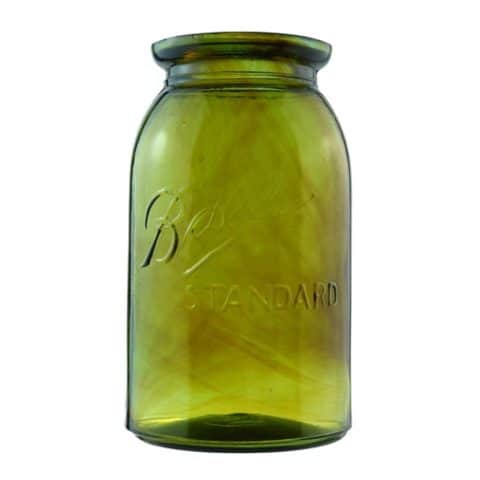

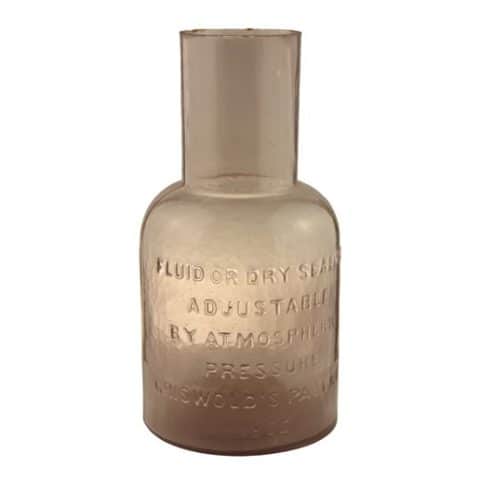

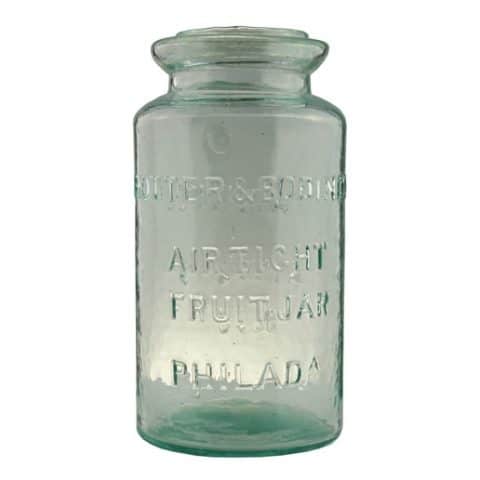

Support Image: Auction: FH5 on base wax sealer quart, yellow-green, applied groove ring wax sealer mouth finish, sparkling glass, has a faint bruise on the inner edge of the outer ring, Embossing: base only, “FH 5”, Age: late 1800s. Rare in this appealing color. The base markings “FH” and “FHGW” have been attributed by Bill Lockhart, et all, to the Frederick Heitz Glass Works of St Louis, MO. – Greg Spurgeon, North American Glass, August 2021

Support Image: 1898 Frederick Heith Glass Works circular – Missouri History Museum, Circulars Collection, Folder 5

Support: Reference to Frederick Heitz and the FHGW Logo by Bill Lockhart, David Whitten, Terry Schaub, Beau Schriever, Bill Lindsey, and Carol Serr

Support: Reference to The Dating Game – The F H G W Mark by Bill Lockhart, David Whitten, Bottles and Extras, Winter, 2006

Support: Reference to Fruit Jar Annual 2020 – The Guide to Collecting Fruit Jars by Jerome J. McCann

Support: Reference to Red Book #11, the Collector’s Guide to Old Fruit Jars by Douglas M. Leybourne, Jr.

Support: Reference to GlassBottleMarks.com

Join the FOHBC: The Virtual Museum is a project of the Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors (FOHBC). To become a member.