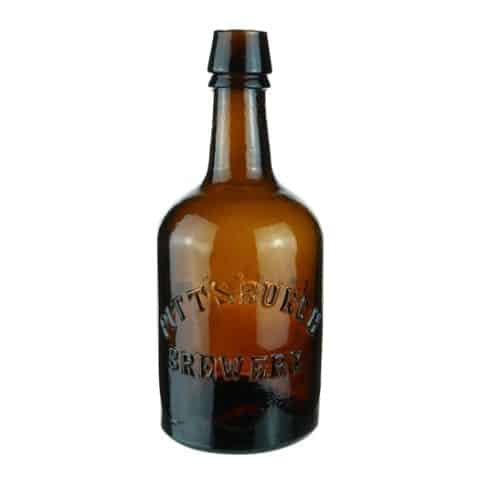

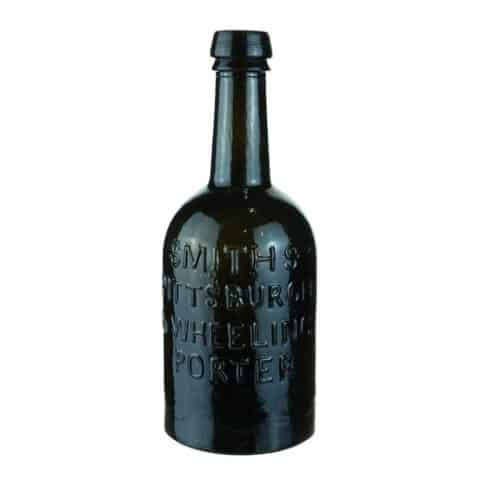

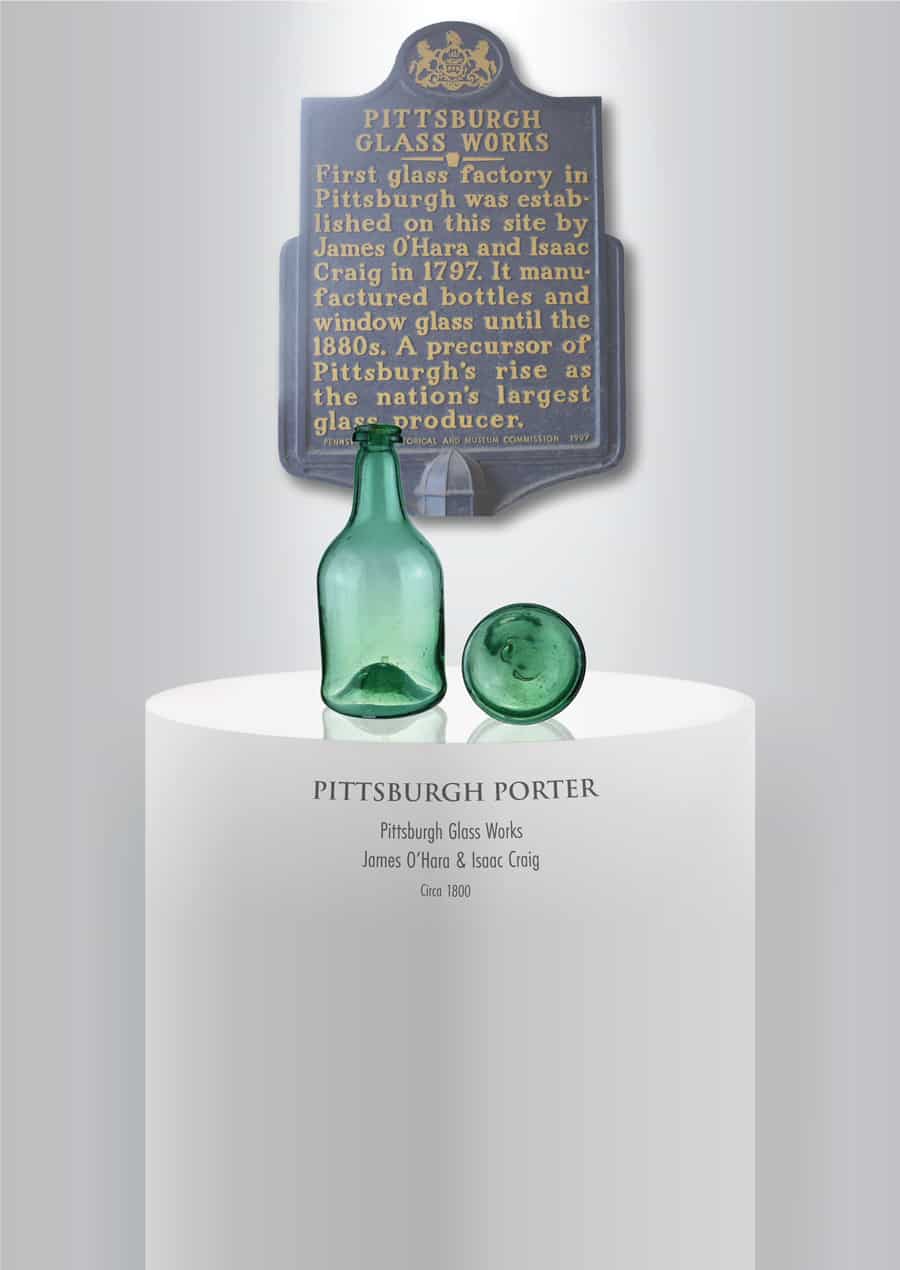

Pittsburgh Porter

Pittsburgh Porter

Attributed to Pittsburgh Glass Works

James O’Hara & Isaac Craig, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

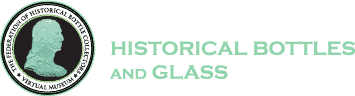

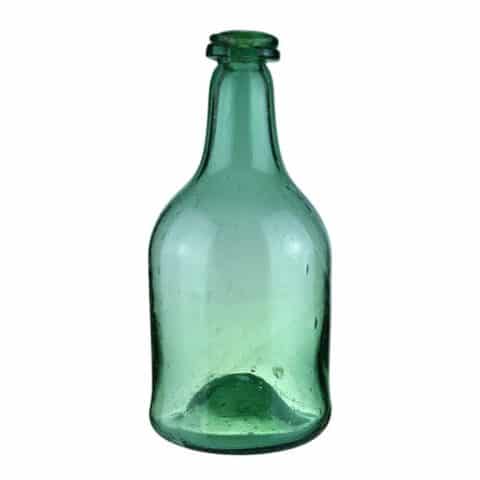

Apple Green Porter Bottle

Provenance: Chip Cable Collection

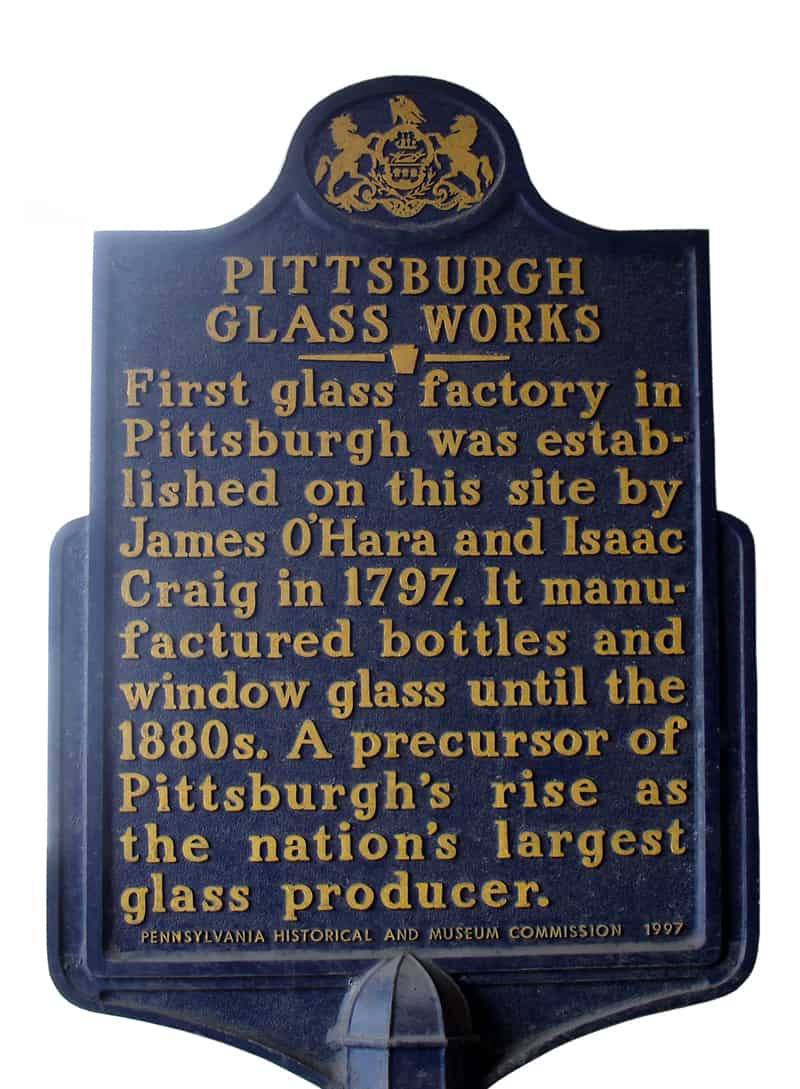

Pittsburgh is known as Iron City and certainly could be Coal City too. Many collectors know Pittsburgh as Glass City. James O’Hara and Isaac Craig started Pittsburgh’s first glasshouse in 1797. At one point, the glass industry in Pittsburgh had ninety glass furnaces sitting beneath overhanging smoke. In these furnaces, exposed to a heat that would equate to Dante’s Inferno, stood eight hundred huge pots in a clear, bright heat and holding a syrupy mass of molten glass.

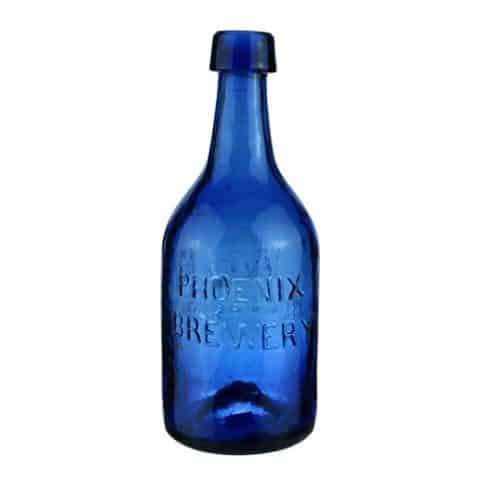

Our subject Porter was found 30 feet below ground level in an old foundation on a Pittsburgh construction site in the 1980s. The consignor found many broken pieces over the years, but this is the only whole example known. The 9 inch tall by 4 inch wide, cylindrical, light blue green Porter-style bottle has an outward rolled mouth on a pinched collar with a laid-on ring. There is a pontil scar.

In October 1795, James O’Hara and Joseph Coppinger, a Porter brewer from Europe, entered into a partnership to obtain barley, rye and wheat for their new Pittsburgh Point Brewery. O’Hara was a gentleman, scholar, capitalist, and quartermaster-general under George Washington. He was also one of the nation’s pioneer glassmen. His first glassworks was built and began to produce glass in 1795, two years before the Gallatin glasshouse at New Geneva, Pennsylvania, was in production. The bottle business was unsuccessful, but he continued making window glass for several months.

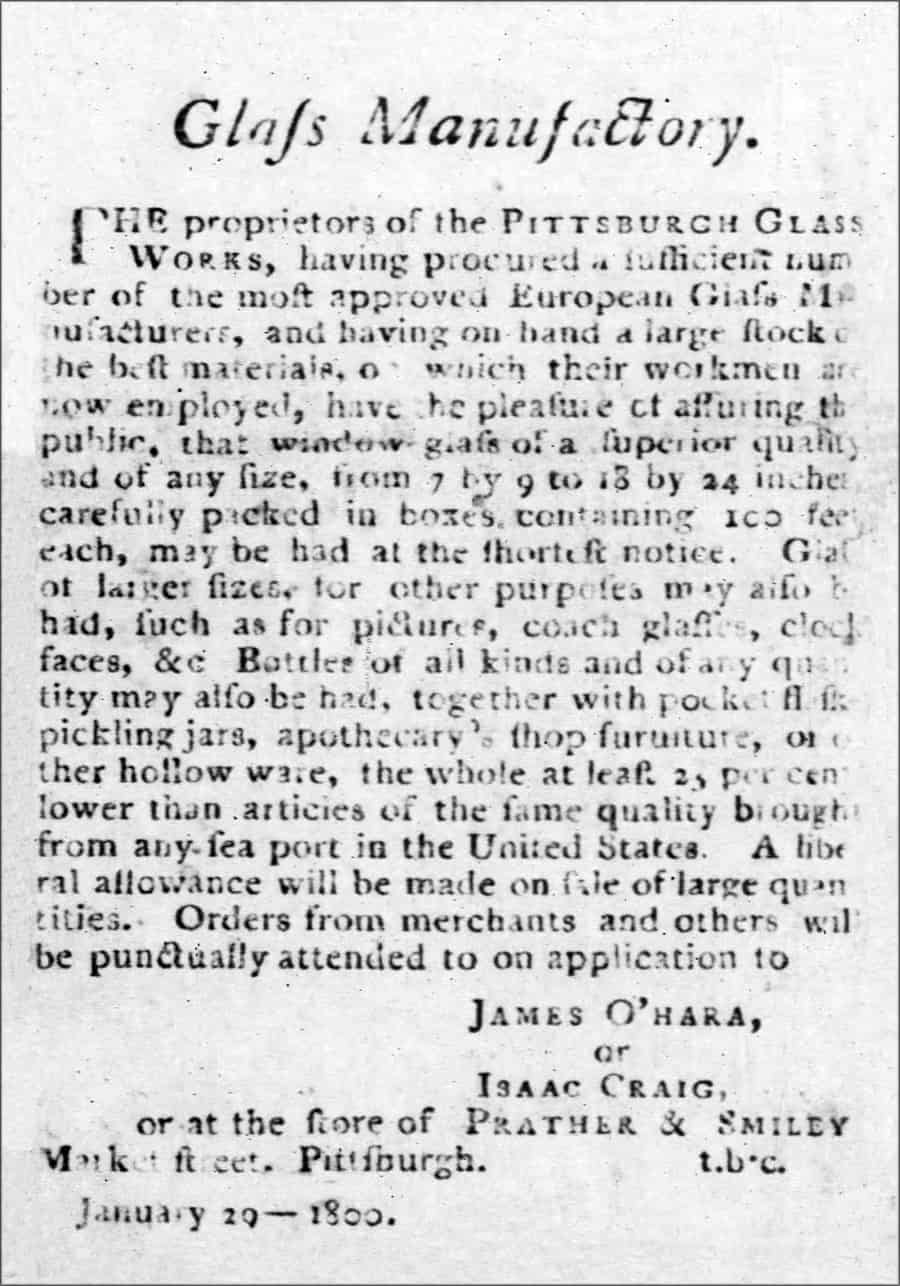

O’Hara concluded that the trouble with the bottle manufacture was insufficient heat for his furnace, and he took steps, with the help of Isaac Craig, to build a new and better glassworks on the west side of the Monongahela River at the foot of Coal Hill. Craig and O’Hara next hired Peter William Eichbaum in Philadelphia in 1796. The new Pittsburgh Glass Works began the successful production of both window glass and bottles in 1797 with Eichbaum as manager and Frederick Wentz (also written Wendt and Wendtz) as superintendent. The glasshouse was making “superior window glass of any size, from 7 by 9 to 13 by 24 inches.” They also made bottles of all kinds and quality, pocket flasks, pickling jars, and apothecary bottles.

The following was extrapolated and condensed from The City of Pittsburgh, Harper’s Magazine, December 1880

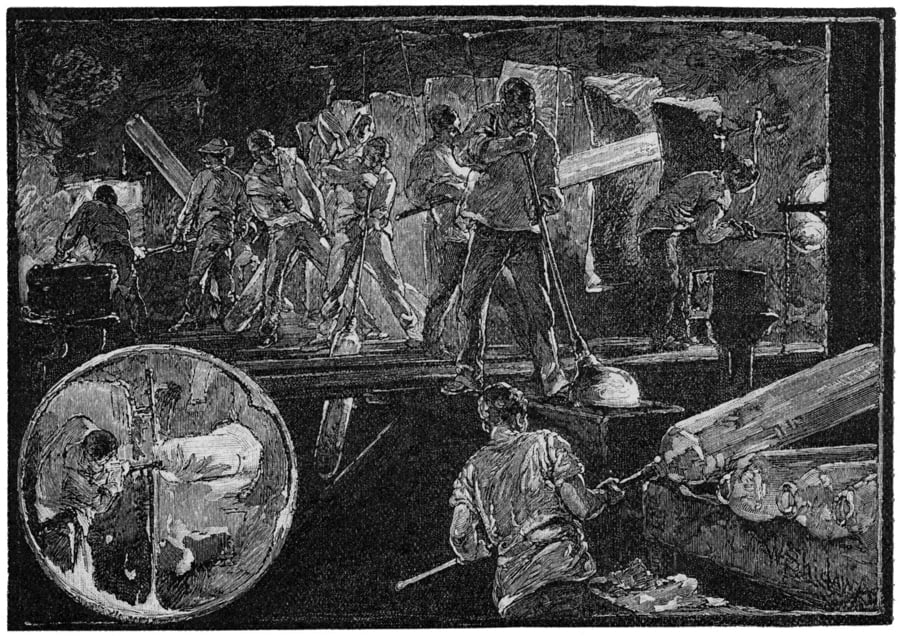

These furnaces, or “glasshouses,” are bulbous pyramids of brick, so encompassed with frame buildings as to their lower three-fourths to closely resemble great square inkstands from a distance. Inwardly they glow with the fervor shown by their neighbors, the iron furnaces. Outwardly they are dusty with sand and lime and suggestive of a country grist-mill. The racket of wheels, however, is conspicuous by its absence. Nor is there puff of escaping steam or hurrying tread of workers; only the tremendous upward roll of deep black smoke from the mouth of the giant ink-bottle chimney and the glare of the furnace.

Internally this glasshouse is almost as full of weird beauty as is the steel melters domain. In and about Pittsburgh’s glass pots and furnaces, there labors an army of five thousand men and boys. These, as to the former, are strong of muscle and stronger of the lung; as to the latter, duly observant of the adage referring to throwing stones in glasshouses and deft in handling fragile things.

A glassblower’s daily duties call for an amount of lung duty that would appall an average person. In this phase of glass-making, i.e., the “blowing” of window and other glass, there has been little or no advance in half a century. Every further advance in the industry has been made wider and smoother by the inventor and the skilled mechanic.

Still, the window-glass factory of 1880 is a counterpoint to the factory of 1825. A straight blow-pipe and a bench are the workman’s appliances. With the former, he dips from the “pot” a lump of sticky melted glass and, if he is a notably good blower, will in five minutes convert that forty-pound lump of cherry-red shapeless stickiness into a splendid cylinder six feet long and fifteen inches in diameter—a cylinder whose polished crystal walls are uniformly thin in every part to the minutest fraction of an inch; so that when this cylinder is split and flattened it will be a mammoth plate of “blown” glass, measuring forty-five by seventy-six or eighty inches. The blower at work challenges admiration as his tremendous lungs force air into the growing bubble at the end of his pipe. Its cooling walls grow thinner, yet the swelling air cell within is never permitted to burst its fragile prison.

As the mass takes on a cylindrical shape, the man calls to his aid the force of gravity, and the pipe becomes a pendulum, with the growing cylinder for a “bob.” And so, by skillful twirling, constant blowing, and laborious but graceful swinging, the perfect cylinder appears. At the same time, the gazer is puzzled about which to most admire, cause or effect, workman or work. The finished cylinder is now split from end to end by the touch of a red-hot bar and, with others, is borne to a queer furnace, whose interior is fitted with a revolving floor like a railway “turn-table.” On this are laid the cylinders, and slowly they are borne through positive and comparative to superlative degrees of heat. The fracture being uppermost, the softening cylinder of its own weight parts along the upper side. A workman, with a bit of soft wood on the end of a rod, then operates on the demoralized cylinder as a laundress would work in ironing a big cuff. The block, pushed over the uneven surface, flattens the cylinder upon its stone bed, where it lies, prone and pretty, like a vast sheet of clear gelatine. A turn of the furnace floor and another cylinder comes within reach of the workman and flattener. At the same time, the same movement carries the finished sheet to a cooler place, eventually finding its way to the cutter, the packer, and the distant customer.

In converting molten glass into tableware, barware, bottles, lamps, and a thousand other objects, improved machinery is springing into existence, each device greeted with more or less disfavor by the workmen. But as yet, no inventor has succeeded in displacing the big-armed, deep-chested “blower.” He defies machinery, lives to a good old age, and surely earns his twenty-five and fifty dollars per week. The latter figure is attained by the few men who can “blow” a sheet of the dimensions already given.

Primary Image: Early Pittsburg Porter bottle imaged on location by Alan DeMaison, FOHBC Virtual Museum Midwest Studio.

Support: Reference to Early Pittsburgh Glass-Houses, Harry Hall White from The Magazine ANTIQUES, November 1926.

Support: Reference to The City of Pittsburgh, Harper’s Magazine, Volume 62, Number 367, December 1880, p63-64.

Support: Reference to The First Glasshouse West of the Alleghenies by Dorathy Daniel

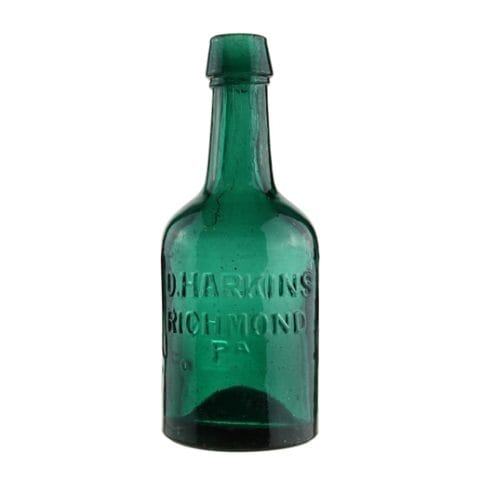

Support Image: Auction Lot 246: Freeblown Porter Bottle, probably early Pittsburgh district, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1820-1840. Cylindrical, light blue green, outward rolled mouth – pontil scar, ht. 6 3/4 inches; (interior washable haze). Similar in form and construction to PG plate 26, right Appealing early form and size. Fine condition. – Norman Heckler Jr. & Sr., Norman C. Heckler & Company, Auction #158

Join the FOHBC: The Virtual Museum is a project of the Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors (FOHBC). To become a member.