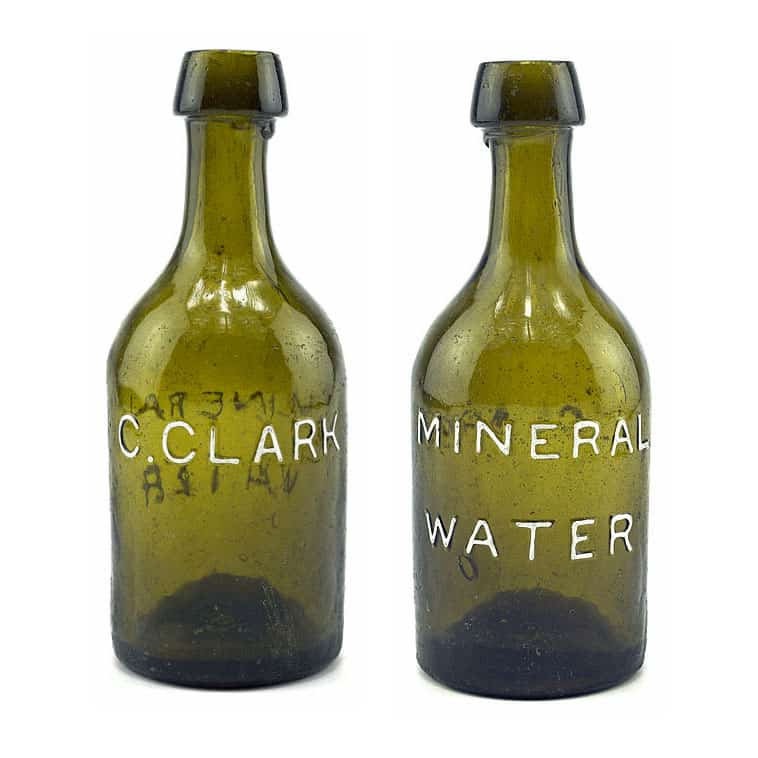

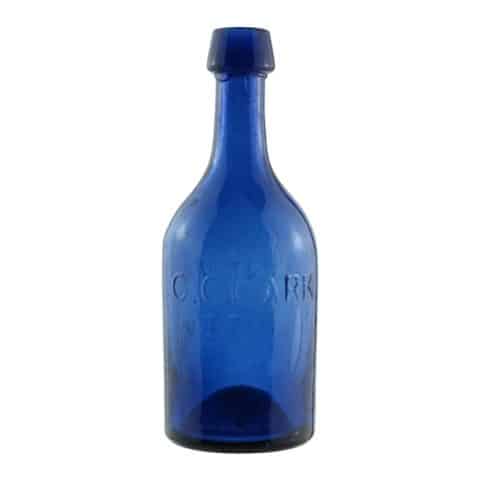

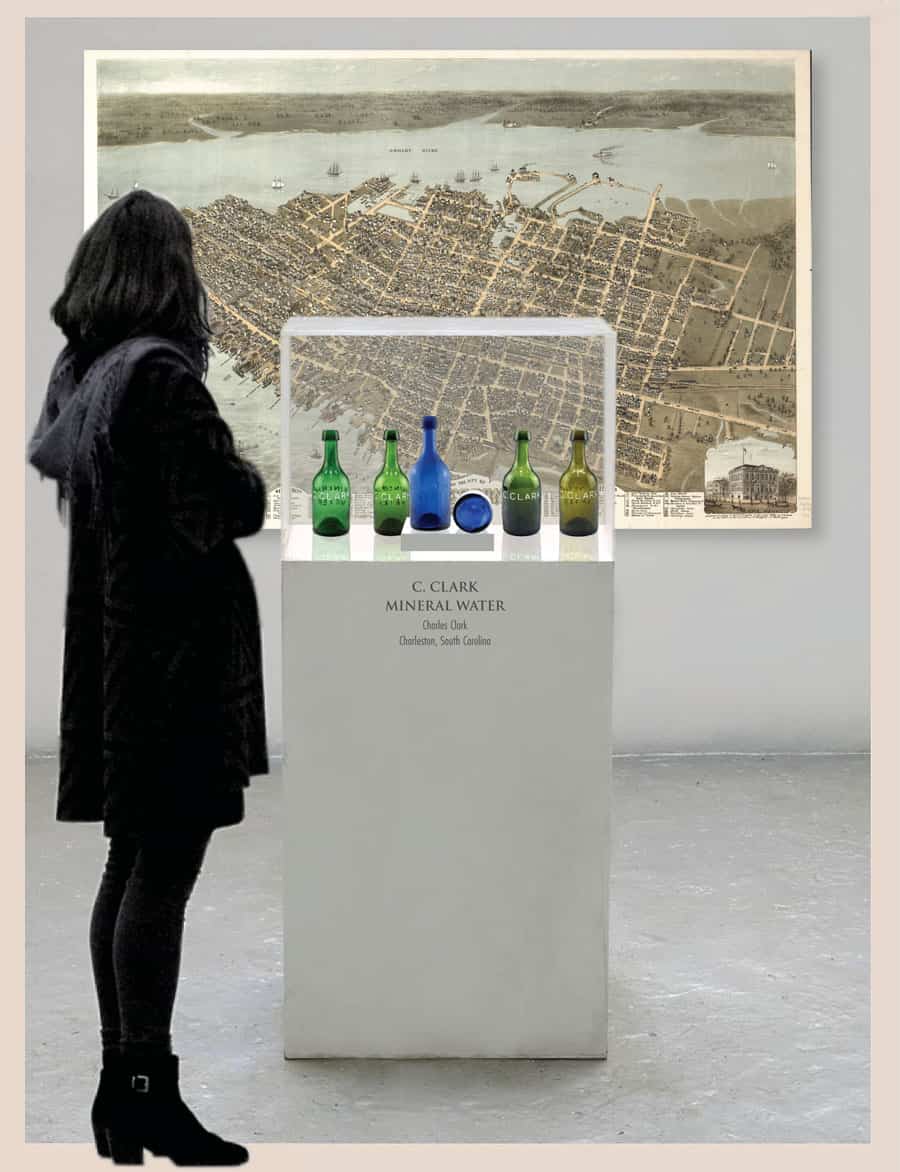

C. Clark Mineral Water

C. Clark

Mineral Water

Charles Clark, Charleston, South Carolina

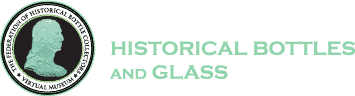

Cobalt Blue Soda Water Bottle

Provenance: Mike Newman Collection

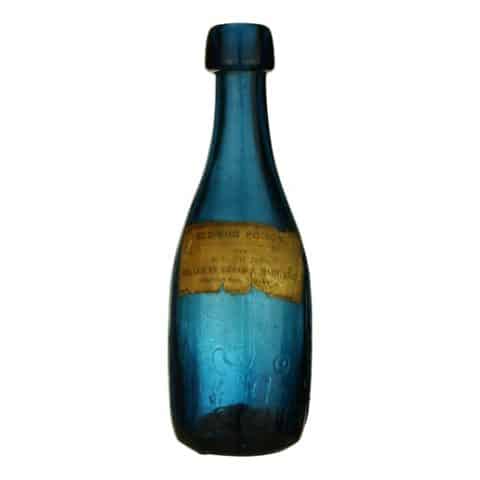

Charles Clark of Massachusetts moved to the antebellum city of Charleston, South Carolina, in the early 1820s. He became a successful grocer and one of Charleston’s most notable druggists and soda water manufacturers. Four different embossed soda water bottles are attributed to Clark, including this cobalt blue “C. Clark Mineral Water.”

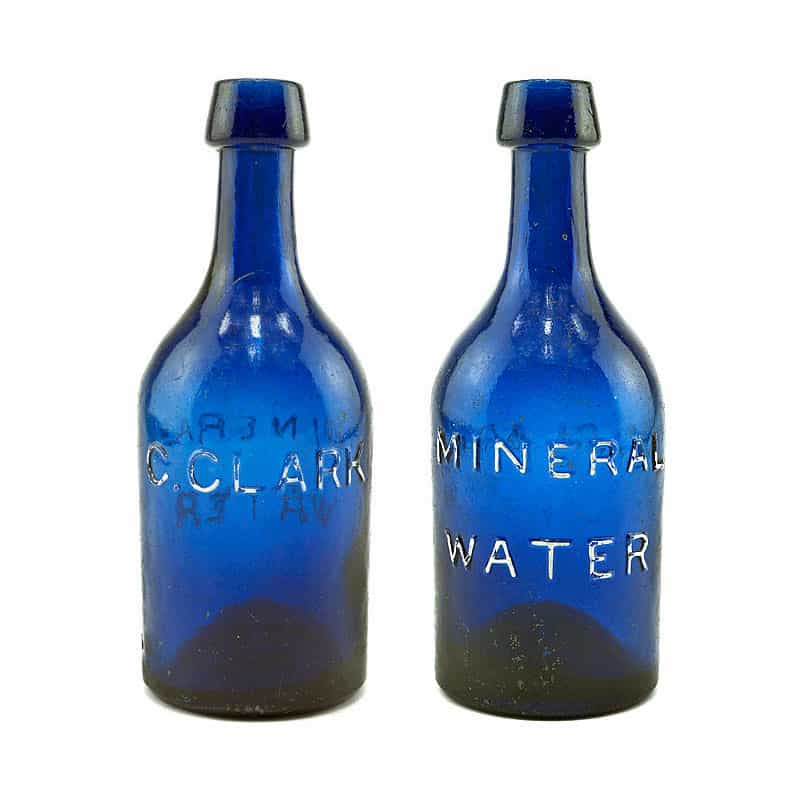

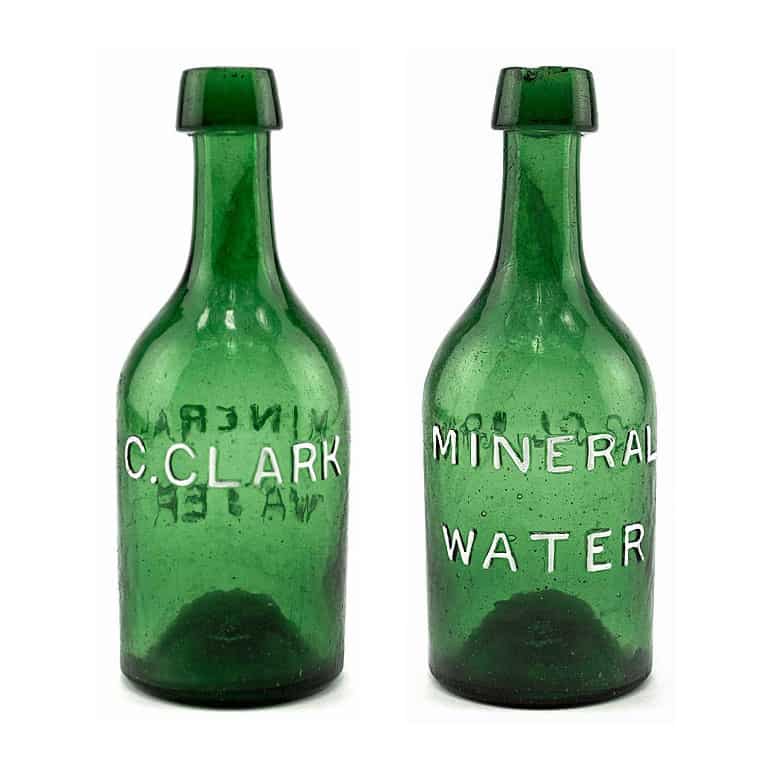

Our cobalt blue museum example is a remarkable example that measures 7 3/16 inches x 2 ¾ (3 ½). The hand-blown form is cylindrical and the shape of a soda water bottle. The pontil is improved. The bottle is embossed in a thin sans serif typestyle ‘C. CLARK’ on the front in one line and ‘MINERAL WATER’ on the reverse in two open-spaced centered lines. The collar is tapered and applied. A cork would have been used to seal the bottle. Besides cobalt blue, the bottle is usually found in shades of green and olive green glass.

Before soft drinks, there was a significant mineral and soda water industry in the United States, populated mainly by regional manufacturers. Water quality was a considerable concern in the antebellum days of cholera epidemics. Mineral or soda water was considered safer than well or other flowing water.

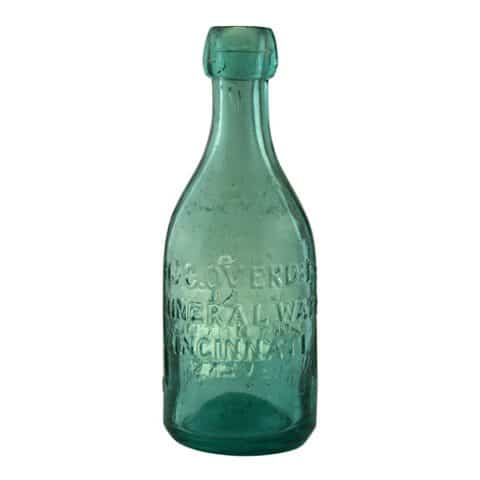

The difference between “soda water” and “mineral water” during the 19th century was often vague. Soda water was generally considered flavored artificial mineral water with the purposeful addition of carbonation and various compounds and flavoring. Mineral or spring water, as it was also called, would generally be natural waters from spring sources that were typically highly mineralized with carbonates like alkaline, sulfurous compounds, and various salts, often carbonated naturally. Confusion sometimes arises when mineral water is used as a generic term applied to various natural and artificially carbonated, non-artificially flavored waters, including many utilized for their perceived medicinal qualities. Please visit the museum Spring & Mineral Water Gallery.

Charles Clark’s success as a druggist and soda water bottler was likely due to his short partnership with and the influence of Doctor Eli Gatchell, a practicing physician and dentist. Gatchell was featured on the cover and in the July–August 2022 issue of Antique Bottle & Glass Collector. Gatchell died young and left soda bottle collectors with only one bottle in a few shades of green. Clark, however, left us with a prodigious amount; at least four different embossed examples in six variant types in colors such as shades of green, blue, and olive that easily number over a dozen bottles. Charleston bottle collector Chip Brewer said the bottles are to be found “in the most colors of any Charleston soda.”

Charles Clark was born June 14, 1790, in Sherborn, Massachusetts, the oldest child of Michael and Lucy (Allen) Clark of the same place. Clark moved to Charleston before 1823. He was likely in his late 20s or early 30s when he opened a grocery store near the City Market.

Back then, Charleston was among the five or six largest cities in the United States, with a population the same as New Orleans and double that of Richmond, its only Southern rivals. In the 1820s, the population of Charleston was 24,780 inhabitants, with more enslaved people than whites.

In 1825, the Charleston City Directory shows Clark had a grocery store at 65 East Bay Street at the corner of Bay and Tradd Streets. At 10 Tradd, he raised a family in a two-story wooden house on a brick foundation, with six upright rooms, a pump in the yard, a stable, garden, and some fruit trees. Clark had a black mistress, and they had two children, John and Henry Clark.

Clark, like other merchants, could not have known that fires would periodically destroy the city. He appears to have been fortunate for a decade until the evening of February 16, 1833, when a great fire swept through the area of East Bay, Market and Anson Streets. This fire destroyed much of the wooden vegetable market, and the pork market is now known as the City Market. A corn warehouse was blown up to stop the fire from crossing Anson Street.

According to the 1837 and 1838 Charleston City Directories, Clark rebuilt or moved to a surviving building, as he was now listed as a grocer at 19 East Bay Street. The house survived the fire and Charles and his mistress had two more children, Elizabeth and Anna Clark.

In 1840, Clark’s grocery moved to 49 Bay Street, and he advertised in The Charleston Daily Courier, wishing to rent his house. Since the children were still young, he might have moved the family living quarters elsewhere or maybe above the grocery. Clark’s grocery remained at 49 Bay Street until 1849 when he formed a partnership with Dr. Eli M. Gatchell and moved to 33 Market Street.

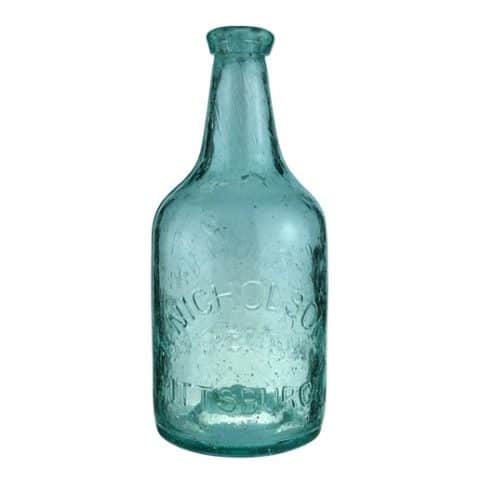

Gatchell had established himself as a physician, apothecary and dentist. It appears he brought in Clark as a partner to make him a druggist and to help with a new venture into soda water manufacturing. The two men partnered, thus becoming Gatchell & Co., and for the first time, Clark started calling himself a druggist. The two used horses and wagons to deliver soda water to their customers.

Gatchell and Clark were only in business for about a year. Gatchell died of unknown causes at age 35 on December 3, 1849. Clark continued as a druggist at the same store on Market Street and placed an ad in the Charleston Courier newspaper informing customers:

“E. M. Gatchell & Co. and those indebted are requested to make immediate payment to Charles Clark, surviving co-partner of E. M. Gatchell & Co. The business will be continued by the subscriber, who feels grateful to his patrons for the liberal encouragement heretofore received and hopes to merit a continuance of the same Charles Clark. Soda water will be delivered as usual, at any part of the city, bottled fresh every day. A good assortment of fresh drugs and medicines on hand. Soda water on draft throughout the year, at the old stand market opposite Anson N. B. Orders from the country promptly attended to.”

The 1850 United States Federal Census of Charleston listed Charles Clark as a druggist owning a drug store with four children and no wife or significant other. Perhaps his mistress had died, or she was just not there. The four children were all listed as mulatto, his sons now in their late 20s and both working as tinners.

During the 1850s, Clark stayed in business at 33 Market Street, selling drugs and soda water. In 1857, he ran an advertisement that revealed a new soda fountain and shows Clark’s salesmanship in attracting customers. The Clark ad said, “The Latest Novelty In The Soda Water Line!” and “Invites his friends and public to call and see a new patent apparatus for dispensing soda water and other cooling drinks, now in operation at his old stand, Market, opposite Anson Street. This machine, for faculty of drawing, and for its refrigerating power and curiosity, exceeds anything in that line ever seen in Charleston. It rivals McAllister’s wonderful bottle, and is attracting crowds of men, women, and children whenever it is used in Northern cities. The proprietor will be happy to explain to soda water dealers, and others interested in its mysterious working and in many advantages. The subscriber gratefully acknowledges the long and liberal patronage he has received and respectfully solicits a continuance of the same. Charles Clark, Drug & Soda Water Establishment, Market, Opposite Anson Street.”

Clark probably started selling sodas from his own bottles soon after Gatchell’s death. The bottles would have been from northern glass factories since few glasshouses were in the south until after the war.

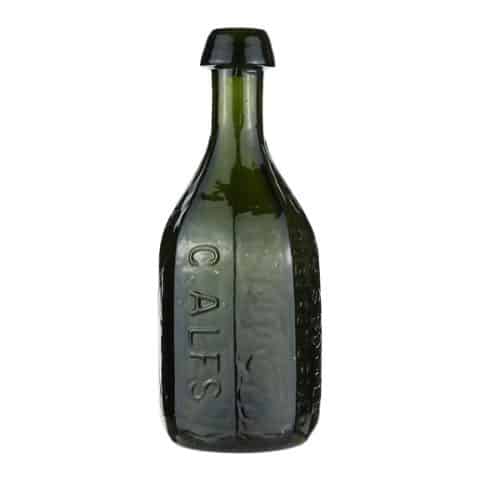

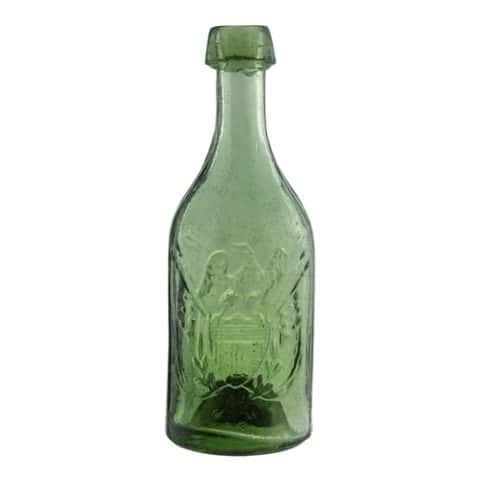

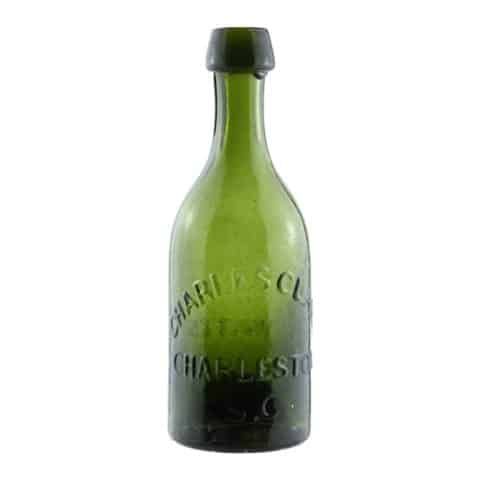

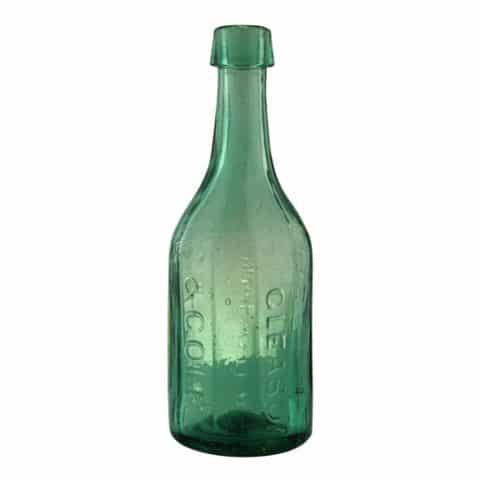

The oldest Clark soda is considered rare. It has a rectangular-shaped, slug plate-embossed ‘C. CLARK’ in arched letters, and ‘CHARLESTON S.C.’ in a straight line below. This bottle stands 7 ½ inches tall and 2 ½ inches wide at the base, coming in various shades of green. Two other Clark bottles have his full name in arched letters, except one bottle is in small letters, the other in large letters. These bottles are embossed, ‘CHARLES CLARK CHARLESTON S.C.’ on the front and ‘SODA WATER’ on the back. Both bottles stand 7 ½ inches tall and 2 ½ inches wide at the base. The small letter Clark is considered rare and comes in various shades of green. The large letter Clark is considered common and comes in various shades of green and rarely in shades of blue.

See the museum example of a “Charles Clark Charleston S.C. Soda Water” bottle.

The 1860 United States Federal Census for Charleston listed Charles Clark as 69 years of age, a soda water bottler, and born in Massachusetts in 1791. Charles had accumulated some wealth and is listed with $3,000 in real estate and $6,000 in personal estate. Also listed in the house with no occupation was Moris Simons, age 33, of South Carolina, and his wife and three children. Moris’ occupation was not given, though he could have been a clerk or drayman working for Clark with living quarters in the rooms once occupied by his children.

In April 1860, at age 69, Clark died of “dropsy” in Charleston. Dropsy was a term used for those who died from soft tissue swelling due to excess water. This is now thought to have been edema, which is said to have been caused by heart, liver or kidney failure.

Death records reveal Clark was a widower and employed as a gardener. The later occupation is surprising because the previous census return indicated Clark was a soda water bottler. This suggests Simons ran the soda water manufacturing business while Clark was tending and planting in the city or at private grounds and estates.

No cemetery or burial records have been found for Clark. However, an inventory of his estate listed a dental chair (probably handed down by Eli Gatchel), some soda water machinery, and other accouterments. The inventory also shows Clark had accumulated some wealth. Personal items such as gold spectacles, a silver watch, confederate cash notes, gold coins, silver coins, as well as shares of stocks from a couple of savings banks were left to his children.

Primary Image: Cobalt blue “C. Clark Mineral Water” bottle imaged on location by Alan DeMaison, FOHBC Virtual Museum Midwest Studio.

Support: Charles Clark research provided by David Kyle Rakes from his forthcoming book on early Carolina soda water bottles.

Support: Reference to Soda & Beer Bottles of North America, Tod von Mechow

Support: Reference to The American Pontiled Soda Database Project, Tod von Mechow

Support: Reference to South Carolina – The Top 25 Bottles by Bill Baab, Bottles and Extras, Summer 2003

Join the FOHBC: The Virtual Museum is a project of the Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors (FOHBC). To become a member.