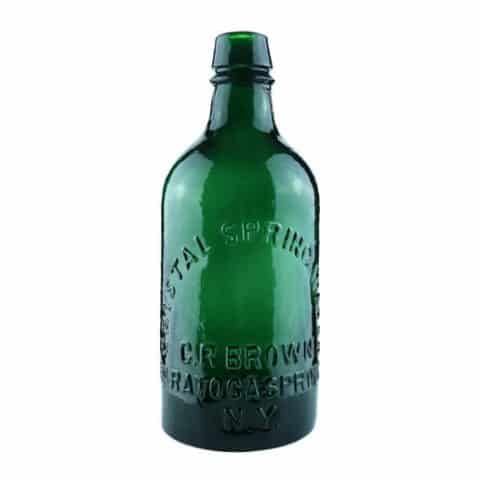

Crystal Spring Water – C.R. Brown

Crystal Spring Water

C. R. Brown

Saratoga Springs N.Y.

Charles Robinson Brown, Saratoga Springs, New York

Emerald Green – Pint

Provenance: Dave Merker Collection

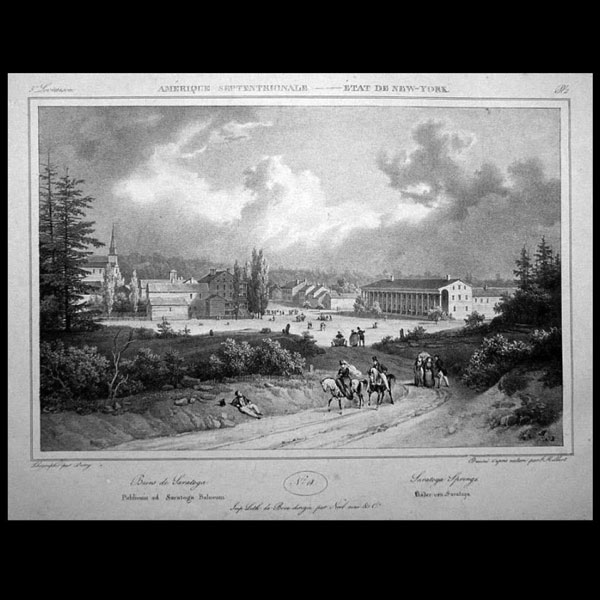

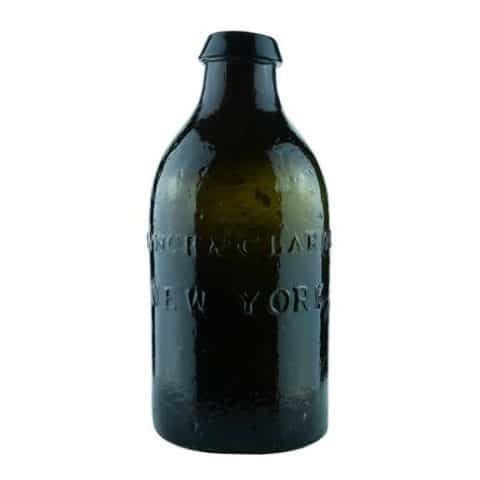

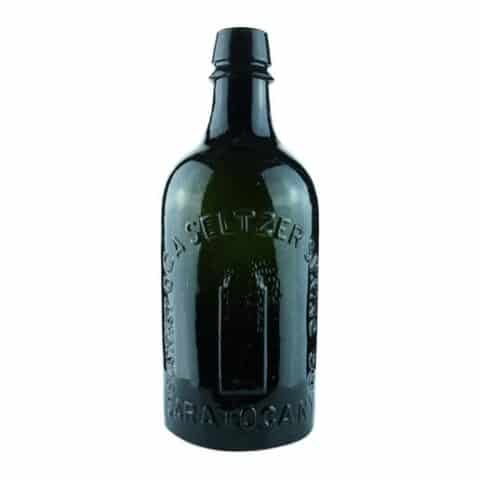

The pint emerald green Crystal Spring bottle in our museum certainly has a story behind it. It was produced and sold in the early 1870s when C. R. Brown used the spring to attract guests to his two hotels.

The bottle is blown in a two-piece hinge mold and has a cylindrical neck and body, a hand-tooled finish with rounded shoulders, and an applied mouth. An arch formed by embossed ‘CRYSTAL SPRING WATER’ typography sets over and encaptures straight line embossed copy in three lines reading ‘C. R. BROWN, SARATOGA SPRING’, and ‘N.Y’. Quart examples exist.

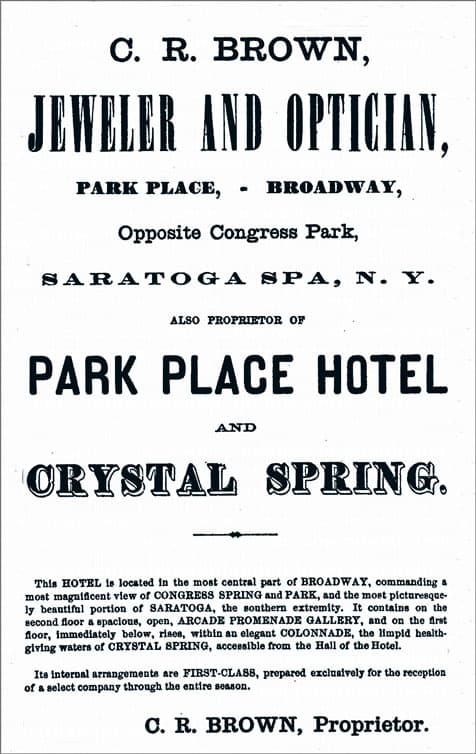

Charles R. Brown was a well-known and successful jeweler in Saratoga Springs, New York. No doubt his many affluent summer visitors afforded him a robust business selling Swiss and American watches, fine jewelry, clocks, diamonds, silverware, opera glasses, eyeglasses, and rings. He would go into the hotel business which was booming in this resort and therapeutic spa town which was only an hour and a half train ride from Albany. He also had his name embossed on a pretty rare Saratoga Springs bottle.

Charles Robinson Brown was born in Unadilla Forks, New York in 1827 and married Mary Ursula Skidmore on August 4, 1854. He has primarily listed as a jeweler and optician until 1871 where we see he was also advertising that he was now the proprietor of Park Place Hotel and Crystal Spring which is the name on his bottle.

C. R. Brown was located at Park Place, Broadway and was opposite Congress Park. His hotel guests overlooked the picturesque Congress Spring and the Park set against a scenic backdrop of Saratoga. An elegant collonade on the first floor of the hotel led guests to the health-giving and therapeutic waters of Crystal Spring. The proprietors named it Crystal Spring from the crystalline appearance of the water, which did not rise to the surface but was pumped up from a depth of several feet. It was discovered in 1870 by experimental excavation.

You can almost picture his jewelry shop prominently facing the street on the ground floor of the hotel. It would have had a second interior entrance facing the lobby of the hotel. A grand display of Crystal Spring bottles would have been set up on covered tables in the hotel lobby and gift shop. Maybe even a retail display of his jewels and pocket watches would have been set up in a glass case with a few bottles of his spring water.

Unfortunately, on September 14, 1871, two very disastrous fires occurred early in the morning, around 2:00 am, destroying the Park Place Hotel, the Columbian Hotel and a large part of the Crescent. All but two buildings were left standing on the block. Charles R. Brown suffered major losses to his jewelry business and hotel. A second fire started at Hamilton alley just east of Broadway. A thick cluster of wooden buildings, one dwelling, half a dozen barns, and one tannery were destroyed. There was a suspicion as to both fire’s origins as they both seemed to start at approximately the same time.

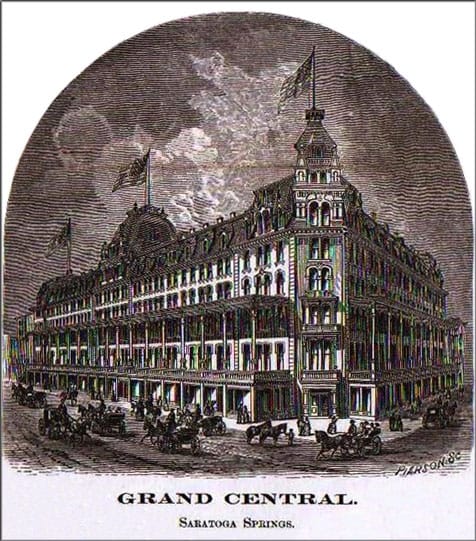

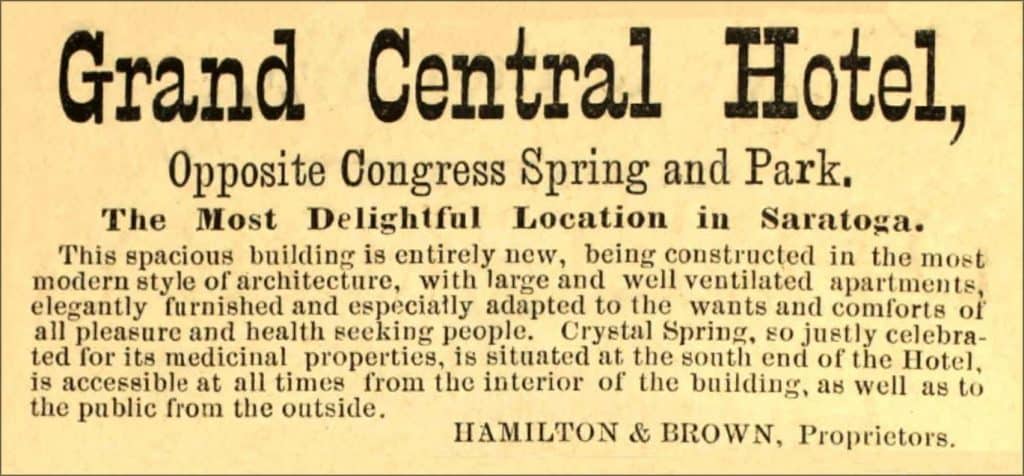

Undaunted by the previous fire that destroyed his hotel, Charles R. Brown went into partnership with Dr. Robert Hamilton, one of the village’s most-respected medical men, to build a new hotel at approximately the same location left bare by the immense conflagration which consumed the Crescent, Park Place and other hotels the previous September. They would build The Grand Central Hotel in record time. It could handle up to 1,000 guests at a time and have access to the same Crystal Spring. He, of course, would set up his jewelry shop within the hotel.

Untiring energy has been manifested in its construction, and it is without doubt one of the most perfect summer hotels in the world. It is a tasteful and elegant structure, adding very much to the beauty and attractiveness of Saratoga. The citizens may well be proud of it. The exterior of the house is most imposing. It is five stories in height, with a French roof, and has a front of 340 feet on Broadway, and 200 feet on Congress street, and by a far-reaching wing in the rear incloses quite a little park.

Saratoga and How to See It, by R. F. Dearborn, 1872

Somehow the partners got the new hotel built and had it opened by the end of July 1872. Unfortunately, they had to stretch their finances to the breaking point. It was reported that Brown and Hamilton ran into money trouble and the property was sold, taken by creditors, and sold again. Some of those owed money placed liens on the furniture and aspects of construction. Still, the Grand Central operated in the summers of 1873 and 1874, closing for what turned out to be the last time in early September 1874.

On October 1st, 1874, disaster would strike again in the form of wood combustion, and by all accounts, it struck in broad daylight this time. “About 11 o’clock yesterday morning, a man on Hamilton Street, passing the Grand [Central] hotel, discovered smoke issuing from the roof of the south wing, containing the dining room.”

The fire’s story was well-accounted for in local newspapers. There were the alerts for more firefighting help telegraphed to Troy, Fort Edward and Glens Falls, only to be countermanded when it was thought the flames would be controlled. The countermand was premature, as it turned out since fire erupted again under the steep Mansard roof, and some observers thought it erupted in more than one place at once. There were strong wind gusts that day as the fire roared and spread. Furnishings from the Grand Central were hauled into the street and stacked up in the Park. The eventual owners’ loss was estimated at $400,000, or about 8 million of today’s dollars.

Blame for the blaze was put on “some malicious person,” and they may have had their motives. It was rumored that many people who worked on the building when it was built had not received their pay and that some unknown person may have burned the building for revenge, one account states. It’s unclear whether anyone was ever arrested.

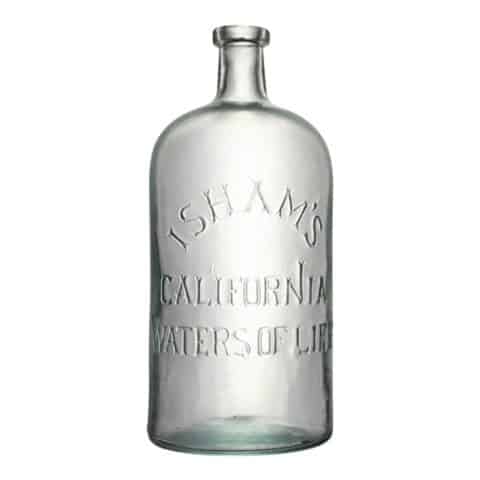

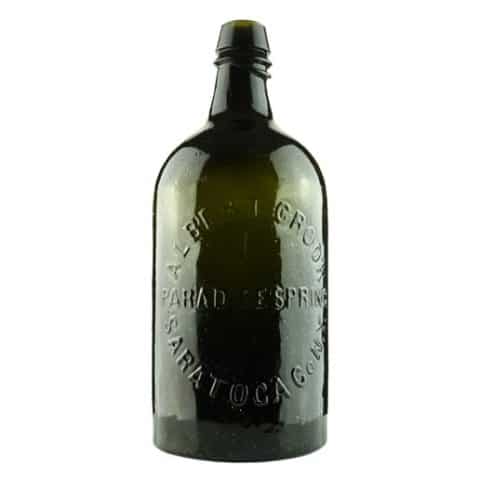

We don’t hear from C. R. Brown much after this second fire event though he was an agent for Bethesda Water, which was located in Waukesha, Wisconsin. He had sold the Crystal Spring but apparently kept the mold and had it peened out to make the Bethesda Water bottle which is pictured in the slide show above. He sold the water through a merchant in Troy, New York. This aqua quart example was the late Howard Dean’s. It is rumored to be one of only two or three known. C. R. Brown died on February 24, 1882, in Saratoga Springs.

Support: French print of the Village of Saratoga Springs, circa 1829

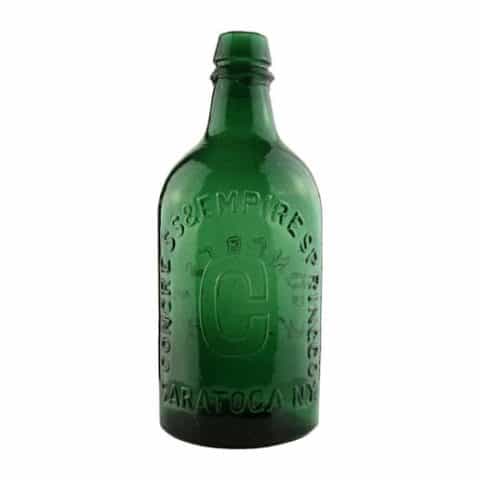

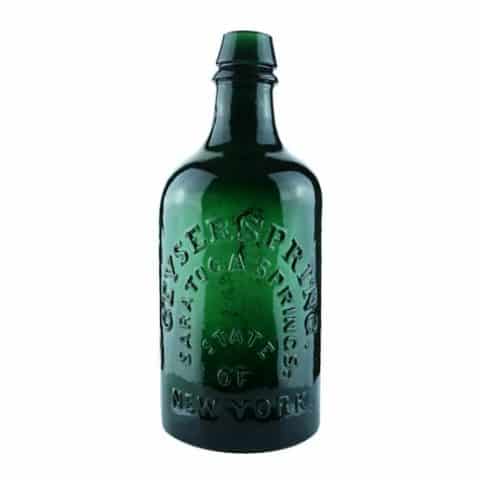

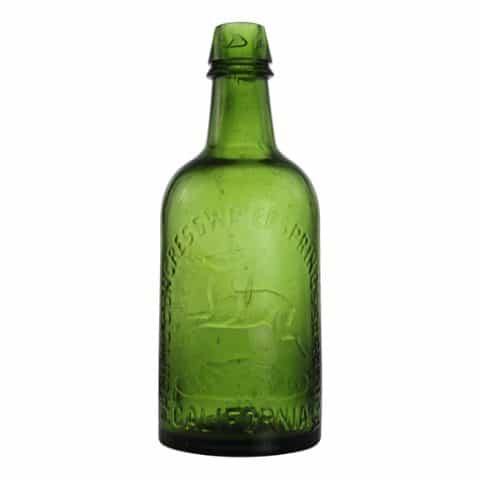

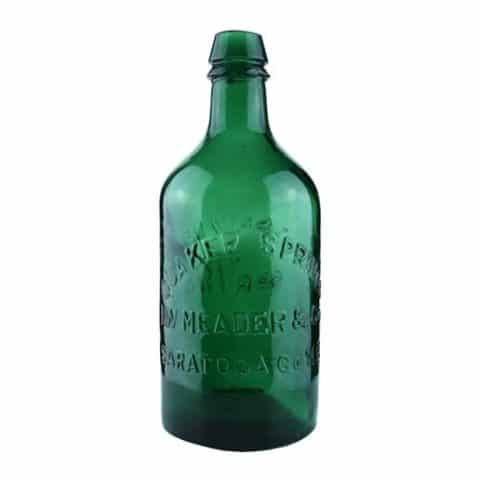

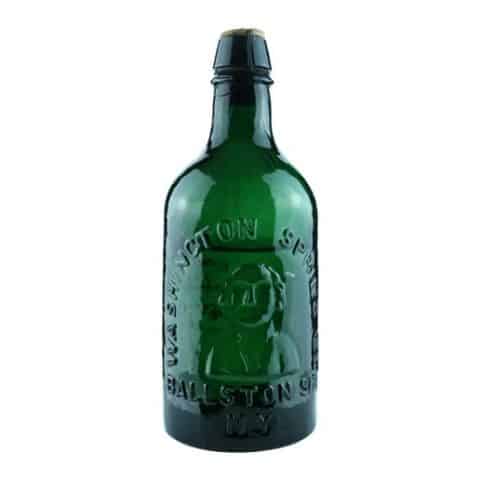

Secondary Bottle Images: Emerald green Crystal Spring Water quart, an older Crystal Spring Water photograph of both the pint and quart together and a photo of the aqua Bethesda Spring quart.

Support: Reference to Collector’s Guide to the Saratoga Type Mineral Water Bottles, Donald Tucker, 1986

Join: The Saratoga type Bottle Collectors Society. Request information at jullman@nycap.rr.com

Join the FOHBC: The Virtual Museum is a project of the Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors (FOHBC). To become a member.